Staff Perspective: A Look at the 2014 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report

This same time last year I shared data from the calendar year 2013 (CY13) Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER). The DoD releases the most up-to-date DoDSER report annually, which summarizes fatal and nonfatal suicide events for U.S. Service members. As someone who is highly interested in suicide prevention and intervention, I anxiously await the release of the new document every year. There is always the desire to see a decrease in suicide rates as well as more information/data that can help us intervene earlier and diminish the devastating impact that suicide has on everyone involved. The most current report for calendar year 2014 (CY14) was released in January.

Although the annual DoDSER report does not have all of the answers, it does provide a wealth of information about suicide events and rates as well as demographic information. The report addresses psychosocial stressors, behavioral health history and deployment history for each suicide event and is used to help inform Service level suicide prevention efforts. We utilize the data here at the Center for Deployment Psychology to help inform our trainings.

Before I jump into the numbers (since I know not everyone loves numbers), I want to point out a few things that are supported by the CY14 DoDSER report that I think are important for us to think about as we work with Service members:

- Military suicide rates are comparable with U.S. civilian suicide rates when adjusted for age and gender (since the makeup of the military is different than the general U.S. population, we have to take this into consideration when looking at suicide data)

- Service members continue to suicide via weapon at higher rates than their civilian counterparts (this is important when we discuss means restriction at a population health level and at a clinical level)

- Failed relationships continues to be the primary psychosocial stressor reported in suicide and suicide attempt DoDSER reports (again, something we can address at a prevention level and a clinical level)

- There was a statistically significant difference in reduction in the prevalence of deployment history for both suicides and suicide attempts compared to CY13 data (although deployment may play a role in suicidal behavior in Service members, it is not the entire story)

- The CY14 DoDSER report was the first to match suicide events against Service members who made an unrestricted report of a sexual assault utilizing data provided by the DoD Sexual Assault Prevention Response Office (SAPRO) (this is important data to be looking at, but it should be noted that this is only a subset of the data and does not include Service members who made a restricted report or who chose not report a sexual assault)

The most recent DoDSER report shows that in CY14 the Active Component suicide rate slightly increased, whereas the Selected Reserve rate decreased. This trend is opposite of what we saw in CY13 where the Active Component had a slight decrease and the Selected Reserve Component had an increase. The Selected Reserve includes both the Reserve and National Guard components and a decrease was seen in both in CY14.

Please note that data for the annual DoDSER report were collected by the Services and augmented by data from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System (AFMES; for active duty suicide decedents) and the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC; for suicide decedents and suicide attempts). The number of completed DoDSERs is lower than actual suicides (total count) since DoDSER submissions were only required for: 1) Suicide events that had been confirmed by 31 Jan 2015, and 2) Service members who were in a duty status at the time of the event.

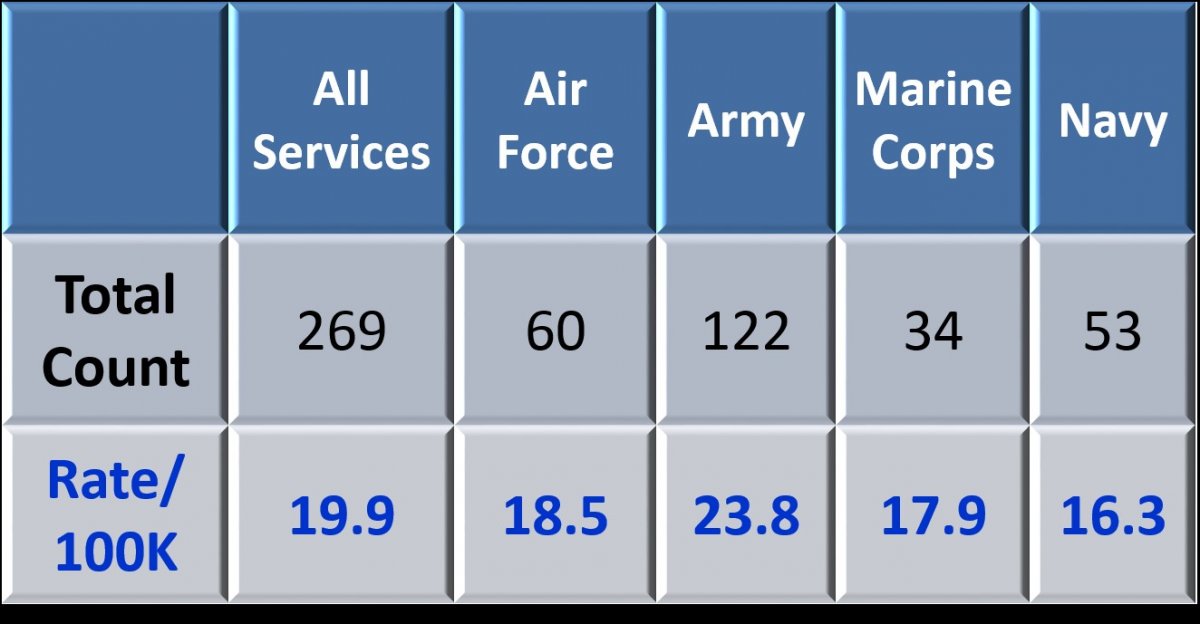

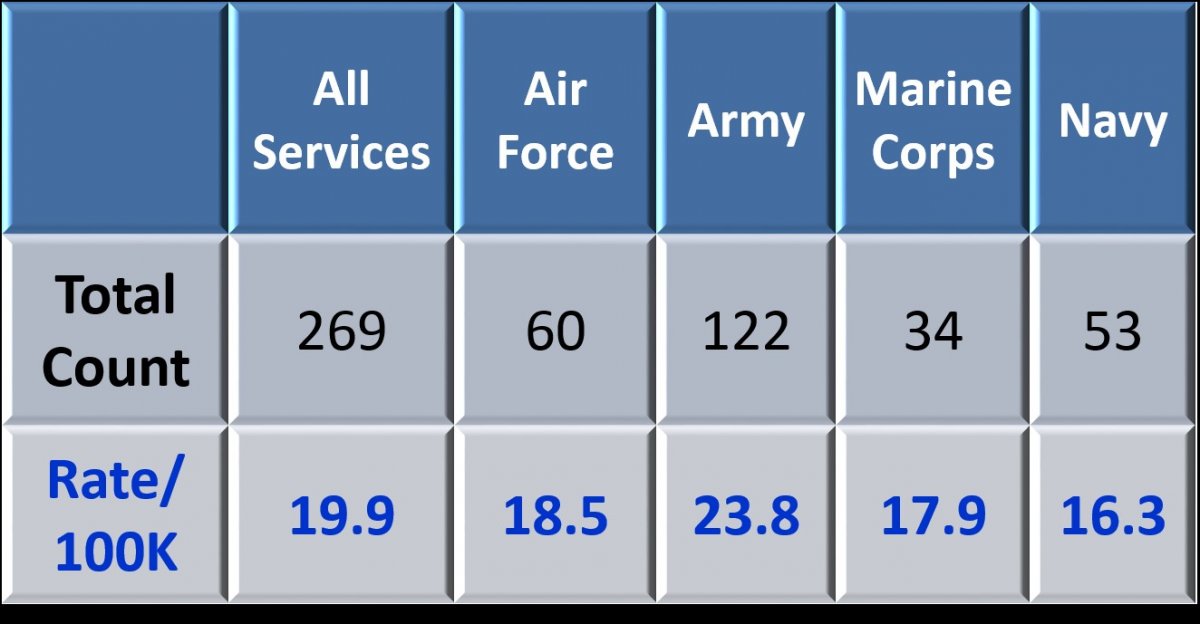

In CY14, there were 269 suicides among Active Component Service members, which is a rate of 19.9 per 100,000 (rates for CY13 and CY12 were 18.4 and 22.9 respectively). The rates in CY14 for the Active Components of the four Services were as follows: 18.5 Air Force, 23.8 Army, 17.9 Marine Corps, and 16.3 Navy (compared to CY13 rates, which were: 14.4 Air Force, 22.5 Army, 23.1 Marine Corps, and 12.7 Navy). Over the past several calendar years we have seen the Army and Marine Corps with the highest rates (the Army had the highest rate in 2011 and 2012 and the Marine Corps had the highest rate in 2013). See Table 1 below for CY14 Active Component suicides and rates.

Table 1. Active Component Suicides and Rates (CY14)

In CY14 there were also 169 suicides among the Selected Reserve components to include 80 suicides for the Reserve Component and 89 for the National Guard Component, which is a rate of 21.9 and 19.4 respectively. The National Guard saw the largest decrease in rate from 28.9 per 100,000 in CY13 to 19.4 per 100,000 in CY14. Per the 2013 DoDSER report, the number of suicides in the Selected Reserve for each Service was too small to calculate stable unadjusted rates with the exception of the Army Reserve (21.4) and Army National Guard (21.5). Numbers reported above for the Reserve and National Guard components are included irrespective of duty status at the time of death.

There were 281 suicide DoDSER reports completed and submitted by the Services for CY14. This includes 261 for the Active Component and 20 for the Selected Reserve Component (11 for the Reserve and 9 for the National Guard). An additional 1,126 suicide attempt DoDSER reports were completed and submitted (1,080 for the Active Component, 20 for the Reserve, and 26 for the National Guard). So what does the DoDSER tell us about Service members who died by suicide or attempted suicide in 2014?

The most common demographic characteristics for Service members who died by suicide in CY14 were: male, white/Caucasian, non-Hispanic, under 30 years of age, enlisted, married, and educated through high school. For suicide attempts, the demographics looked very similar, although there were more junior enlisted (E1-E4) who attempted and for marital status there was approximately an even distribution between never married and married.

For suicide DoDSERs, the most prevalent method was gunshot (68.3%), of which most (92.2%) were by non-military issued firearms, followed by hanging/asphyxiation (24.9%). For suicide attempt DoDSERs, the most prevalent method was use of drugs and/or alcohol overdose (56.2%).

The most common behavioral health diagnoses for suicide DoDSERs were mood disorders (26.3%), adjustment disorders (24.2%), and history of substance abuse (22.1%). For suicide attempt, DoDSERs the most common behavioral health diagnoses were mood disorders (32.9%), history of substance abuse (27.4%), and adjustment disorders (27.1%). Regarding treatment, 60.9% of suicide decedents and 67.0% of those who made a suicide attempt accessed health or social services in the last 90 days prior to the event. Psychotropic medications had been used in the last 90 days by 19.6% of suicide decedents and 33.7% of those who made a suicide attempt.

As we have seen in prior years, the most common psychosocial factor for both suicides and suicide attempt DoDSERs was a failed relationship (42.0% for suicides and 42.9% for suicide attempts), and primarily a relationship that was intimate in nature. Following relationship problems, the two most common psychosocial stressors were having administrative/legal problems within the last 90 days (32.7% for suicides and 32.9% for suicide attempts) and having workplace difficulties within the last 90 days (19.9% for suicides and 35.8% for suicide attempts).

Looking at deployment related factors, 54.4% of suicide DoDSERs and 39.4% of suicide attempt DoDSERs had a history of deployment (with the majority of both categories having only one deployment). In addition, 14.6% of suicide DoDSERs and 15.4% of suicide attempt DoDSERs had direct combat histories. There were eight suicide DoDSERs completed for suicides that occurred in theater (2.8%) and 28 suicide attempt DoDSERs completed for suicide attempts that occurred in theater (2.5%). Over the past several years, both suicide and suicide attempts in theater have decreased.

Of suicide decedents, 23.5% left a suicide note compared to 13.2% of those who made a suicide attempt. The percent for suicide decedents is comparable to what we see in the U.S. civilian population.

This was the first year that DoDSER cases were matched against unrestricted sexual assault reporting data by SAPRO analysts to address the relationship between suicide and sexual assault. According to the CY14 DoDSER report, there were no suicides and 28 suicide attempts associated with an unrestricted report of sexual assault during the year prior to the event. As mentioned above and as pointed out in the CY14 DoDSER report, this is only a subset of data and is not inclusive of all sexual assault cases.

Although the DoDSER cannot capture all suicide event data, I do think that it is an important surveillance system that is helping guide the Services and other professionals as we look at ways to provide suicide prevention and intervention services to our Service members. I have provided only a brief snapshot of what is included in the 2014 DoDSER report. For more information I encourage you to look at the entire report, which can be accessed at: http://t2health.dcoe.mil/sites/default/files/CY-2014-DoDSER-Annual-Repor...

References:

Pruitt, L.D., Smolenski, D.J., Reger, M.A., Bush, N.E., Skopp, N.A., & Campise, R.L. (2015). Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2014 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology and Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health & Traumatic Brain Injury.

Smolenski, D.J., Reger, M.A., Bush, N.E., Skopp, N.A., Zhang, Y., & Campise, R.L. (2014). Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2013 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology and Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health & Traumatic Brain Injury.

Lisa French, Psy.D. is the Assistant Director of Military Training Programs at the Center for Deployment Psychology (CDP) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland.

This same time last year I shared data from the calendar year 2013 (CY13) Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER). The DoD releases the most up-to-date DoDSER report annually, which summarizes fatal and nonfatal suicide events for U.S. Service members. As someone who is highly interested in suicide prevention and intervention, I anxiously await the release of the new document every year. There is always the desire to see a decrease in suicide rates as well as more information/data that can help us intervene earlier and diminish the devastating impact that suicide has on everyone involved. The most current report for calendar year 2014 (CY14) was released in January.

Although the annual DoDSER report does not have all of the answers, it does provide a wealth of information about suicide events and rates as well as demographic information. The report addresses psychosocial stressors, behavioral health history and deployment history for each suicide event and is used to help inform Service level suicide prevention efforts. We utilize the data here at the Center for Deployment Psychology to help inform our trainings.

Before I jump into the numbers (since I know not everyone loves numbers), I want to point out a few things that are supported by the CY14 DoDSER report that I think are important for us to think about as we work with Service members:

- Military suicide rates are comparable with U.S. civilian suicide rates when adjusted for age and gender (since the makeup of the military is different than the general U.S. population, we have to take this into consideration when looking at suicide data)

- Service members continue to suicide via weapon at higher rates than their civilian counterparts (this is important when we discuss means restriction at a population health level and at a clinical level)

- Failed relationships continues to be the primary psychosocial stressor reported in suicide and suicide attempt DoDSER reports (again, something we can address at a prevention level and a clinical level)

- There was a statistically significant difference in reduction in the prevalence of deployment history for both suicides and suicide attempts compared to CY13 data (although deployment may play a role in suicidal behavior in Service members, it is not the entire story)

- The CY14 DoDSER report was the first to match suicide events against Service members who made an unrestricted report of a sexual assault utilizing data provided by the DoD Sexual Assault Prevention Response Office (SAPRO) (this is important data to be looking at, but it should be noted that this is only a subset of the data and does not include Service members who made a restricted report or who chose not report a sexual assault)

The most recent DoDSER report shows that in CY14 the Active Component suicide rate slightly increased, whereas the Selected Reserve rate decreased. This trend is opposite of what we saw in CY13 where the Active Component had a slight decrease and the Selected Reserve Component had an increase. The Selected Reserve includes both the Reserve and National Guard components and a decrease was seen in both in CY14.

Please note that data for the annual DoDSER report were collected by the Services and augmented by data from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System (AFMES; for active duty suicide decedents) and the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC; for suicide decedents and suicide attempts). The number of completed DoDSERs is lower than actual suicides (total count) since DoDSER submissions were only required for: 1) Suicide events that had been confirmed by 31 Jan 2015, and 2) Service members who were in a duty status at the time of the event.

In CY14, there were 269 suicides among Active Component Service members, which is a rate of 19.9 per 100,000 (rates for CY13 and CY12 were 18.4 and 22.9 respectively). The rates in CY14 for the Active Components of the four Services were as follows: 18.5 Air Force, 23.8 Army, 17.9 Marine Corps, and 16.3 Navy (compared to CY13 rates, which were: 14.4 Air Force, 22.5 Army, 23.1 Marine Corps, and 12.7 Navy). Over the past several calendar years we have seen the Army and Marine Corps with the highest rates (the Army had the highest rate in 2011 and 2012 and the Marine Corps had the highest rate in 2013). See Table 1 below for CY14 Active Component suicides and rates.

Table 1. Active Component Suicides and Rates (CY14)

In CY14 there were also 169 suicides among the Selected Reserve components to include 80 suicides for the Reserve Component and 89 for the National Guard Component, which is a rate of 21.9 and 19.4 respectively. The National Guard saw the largest decrease in rate from 28.9 per 100,000 in CY13 to 19.4 per 100,000 in CY14. Per the 2013 DoDSER report, the number of suicides in the Selected Reserve for each Service was too small to calculate stable unadjusted rates with the exception of the Army Reserve (21.4) and Army National Guard (21.5). Numbers reported above for the Reserve and National Guard components are included irrespective of duty status at the time of death.

There were 281 suicide DoDSER reports completed and submitted by the Services for CY14. This includes 261 for the Active Component and 20 for the Selected Reserve Component (11 for the Reserve and 9 for the National Guard). An additional 1,126 suicide attempt DoDSER reports were completed and submitted (1,080 for the Active Component, 20 for the Reserve, and 26 for the National Guard). So what does the DoDSER tell us about Service members who died by suicide or attempted suicide in 2014?

The most common demographic characteristics for Service members who died by suicide in CY14 were: male, white/Caucasian, non-Hispanic, under 30 years of age, enlisted, married, and educated through high school. For suicide attempts, the demographics looked very similar, although there were more junior enlisted (E1-E4) who attempted and for marital status there was approximately an even distribution between never married and married.

For suicide DoDSERs, the most prevalent method was gunshot (68.3%), of which most (92.2%) were by non-military issued firearms, followed by hanging/asphyxiation (24.9%). For suicide attempt DoDSERs, the most prevalent method was use of drugs and/or alcohol overdose (56.2%).

The most common behavioral health diagnoses for suicide DoDSERs were mood disorders (26.3%), adjustment disorders (24.2%), and history of substance abuse (22.1%). For suicide attempt, DoDSERs the most common behavioral health diagnoses were mood disorders (32.9%), history of substance abuse (27.4%), and adjustment disorders (27.1%). Regarding treatment, 60.9% of suicide decedents and 67.0% of those who made a suicide attempt accessed health or social services in the last 90 days prior to the event. Psychotropic medications had been used in the last 90 days by 19.6% of suicide decedents and 33.7% of those who made a suicide attempt.

As we have seen in prior years, the most common psychosocial factor for both suicides and suicide attempt DoDSERs was a failed relationship (42.0% for suicides and 42.9% for suicide attempts), and primarily a relationship that was intimate in nature. Following relationship problems, the two most common psychosocial stressors were having administrative/legal problems within the last 90 days (32.7% for suicides and 32.9% for suicide attempts) and having workplace difficulties within the last 90 days (19.9% for suicides and 35.8% for suicide attempts).

Looking at deployment related factors, 54.4% of suicide DoDSERs and 39.4% of suicide attempt DoDSERs had a history of deployment (with the majority of both categories having only one deployment). In addition, 14.6% of suicide DoDSERs and 15.4% of suicide attempt DoDSERs had direct combat histories. There were eight suicide DoDSERs completed for suicides that occurred in theater (2.8%) and 28 suicide attempt DoDSERs completed for suicide attempts that occurred in theater (2.5%). Over the past several years, both suicide and suicide attempts in theater have decreased.

Of suicide decedents, 23.5% left a suicide note compared to 13.2% of those who made a suicide attempt. The percent for suicide decedents is comparable to what we see in the U.S. civilian population.

This was the first year that DoDSER cases were matched against unrestricted sexual assault reporting data by SAPRO analysts to address the relationship between suicide and sexual assault. According to the CY14 DoDSER report, there were no suicides and 28 suicide attempts associated with an unrestricted report of sexual assault during the year prior to the event. As mentioned above and as pointed out in the CY14 DoDSER report, this is only a subset of data and is not inclusive of all sexual assault cases.

Although the DoDSER cannot capture all suicide event data, I do think that it is an important surveillance system that is helping guide the Services and other professionals as we look at ways to provide suicide prevention and intervention services to our Service members. I have provided only a brief snapshot of what is included in the 2014 DoDSER report. For more information I encourage you to look at the entire report, which can be accessed at: http://t2health.dcoe.mil/sites/default/files/CY-2014-DoDSER-Annual-Repor...

References:

Pruitt, L.D., Smolenski, D.J., Reger, M.A., Bush, N.E., Skopp, N.A., & Campise, R.L. (2015). Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2014 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology and Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health & Traumatic Brain Injury.

Smolenski, D.J., Reger, M.A., Bush, N.E., Skopp, N.A., Zhang, Y., & Campise, R.L. (2014). Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2013 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology and Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health & Traumatic Brain Injury.

Lisa French, Psy.D. is the Assistant Director of Military Training Programs at the Center for Deployment Psychology (CDP) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland.