Staff Perspective: In Support of Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (Part 1)

Recently, we at the Center for Deployment Psychology have been receiving a number of consultation requests regarding translating the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBTI) package to a group setting. If you have been thinking about starting a CBTI group, allow me to increase your motivation and give you some resources to get started.

Let’s start by addressing what is probably a primary concern we have as providers when considering a new treatment approach: is this treatment effective? If you have attended one of our CBTI workshops, you know that individual treatment has clearly and repeatedly been demonstrated to be effective (and if you have not, we encourage you to visit our Training page here and sign up for one!). A timely meta-analysis published earlier this year documents effectiveness for CBTI group outcomes as well (Koffel et al, 2015).

The sleep-related outcomes that we consider important in CBTI can be separated into two categories, sleep quantity and sleep quality. As you may be familiar, patients with insomnia may initially focus on sleep quantity when seeking treatment, but CBTI aims to improve quality first by consolidating the patient’s sleep time. Additionally, some studies have observed that there are secondary outcomes that improve in CBTI as well, such as mood, nightmares or even pain in patients with co-morbid medical conditions, despite the fact that these variables are not targeted by CBTI.

One thing we know about CBTI is that outcomes are not only positive immediately post-treatment, but that they also persist long term, and in some cases, may even continue to improve over time after treatment discontinuation. Accordingly, in addition to reporting effect sizes for sleep quantity, sleep quality, and secondary outcomes, which included measures of mood and pain for the studies in which those were available, the group meta-analysis also included pre- to post-treatment as well as follow-up comparisons. Although follow-up differed by individual study, the range was 3 to 12 months.

The sample included eight RCTs with a total of 659 patients at baseline. Patients with co-morbid medical conditions were included in the sample, although unfortunately patients with co-morbid mental health conditions were not.

As you review the findings, keep in mind that when we evaluate effect sizes, a small effect size is generally considered to be around .2, a medium effect size around .5, and a large effect size .8 and higher. In looking at pre- to post-treatment change, and pre-treatment to follow-up change, the meta-analysis found the following effect sizes.

Group Pre- to Post-Treatment Effect Size

Group Follow-Up Effect Size

Sleep Efficiency (SE)

1.13

.85

Sleep Onset Latency (SOL)

.77

.60

Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO)

.89

.63

Total Sleep Time (TST)

.29

.60

Subjective Sleep Quality

.85

1.26

Subjective Depression

.26

.32

Subjective Pain

.25

.41

I would like to point out that even while some outcomes had reduced effect sizes by the time of follow-up data collection, all effect sizes for the primary outcomes were still medium to large! That is, the majority of primary group outcomes were sustained over the long term, up to 12 months. Moreover, take a look at total sleep time (TST) and sleep quality-these effect sizes actually increased over the long term. Patients continue to improve the amount of sleep they get and how refreshed they feel after sleep once group CBTI has ended.

It gets better. Look at the last two rows, or the secondary outcomes. These were small at post-treatment, but increased by follow-up. While neither outcome reached a medium effect size, consider that this treatment was only designed to target insomnia. The improvement in mood and pain is an additional benefit. In my opinion, so far it seems there is nothing to be lost and a lot to gain from a trial of group CBTI. Hopefully, your motivation to start a CBTI group is increasing!

But wait, you may be thinking, “statistical improvement looks all well and good, but what does this mean for the patients?” Let’s break down these effect sizes into more real-life definitions. For example, the average baseline sleep efficiency (SE) went from 70 to 83% by post-treatment, and hovered at 80% at follow-up. The average sleep onset latency (SOL) went from 53 to 26 minutes by post-treatment, staying within the normal range at 30 minutes at follow-up. Similarly, the average wake after sleep onset (WASO) time went from 78 to 36 minutes by post-treatment, and then to 54 minutes at follow-up. Finally, the TST went from 340 to 359 minutes by post-treatment, then jumped to 374 minutes at follow-up. These numbers more concretely demonstrate that improvements after group CBTI are for the most part sustained, albeit without longer term (over a year) follow-up to conclusively confirm this. My interpretation is that as patients adjust their sleep schedules on their own sleep time continues to improve, but they may trade-off some time awake in bed in an effort to do so.

Overall Baseline

Group Baseline

Overall

Post-Treatment

Change

Group

Post-Treatment Change

Sleep Efficiency (SE)

71.8%

69.51%

9.91%

13.81%

Sleep Onset Latency (SOL)

57.6 min

52.75 min

-19.03 min

-27.25 min

Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO)

76 min

77.54 min

-26 min

-41.38 min

Total Sleep Time (TST)

344.1 min

340.18 min

7.61 min

18.80 min

Of interest, I’ve created a table comparing the outcomes specifically from group CBTI to a meta-analysis of CBTI interventions in general, including both individual and group settings (Trauer et al, 2015), although I would strongly caution that as these data were not designed for direct comparison no firm conclusions should be made.

Note that I did not include the long term follow-up improvements, because the two meta-analyses calculated long term differently (eg, lumped as one large range vs broken down into several time intervals). While the overall CBTI meta-analysis includes group data which to some extent muddies the waters for interpretations, and while it is likely that groups tend to enroll lower complexity patients which potentially allows for greater range of improvement, we can certainly see the suggestion that group outcomes can be similarly effective to general CBTI outcomes including individual treatment.

Whew, that is a lot of data! If you have stuck with me thus far, I hope you are now convinced that group CBTI can be an effective treatment approach within the continuum of care for insomnia. Fortunately, in practice, group CBTI is comprised of a straightforward yet flexible structure that lends itself to implementation in a variety of settings. For example, in Koffel and colleagues’ group meta-analysis (2015), the number of group sessions ranged from 4 to 8, and the length of group sessions ranged from 60 to 120 minutes. While the study authors determined that a greater total number of minutes of treatment was related to greater improvement in sleep, other studies have shown that as few as two group sessions can improve sleep (Edinger & Sampson, 2003).

We recommend tailoring your group’s length and number of sessions to your clinic’s needs. In a primary care setting, two sessions may be more feasible, whereas in a high-acuity or inpatient setting, six to eight sessions offers more opportunity to address any challenges that may arise. In a military treatment facility (MTF) where classes may be offered on a monthly basis, a four-session approach may offer a good fit. Still other clinics may consider an open-format continuous CBTI group.

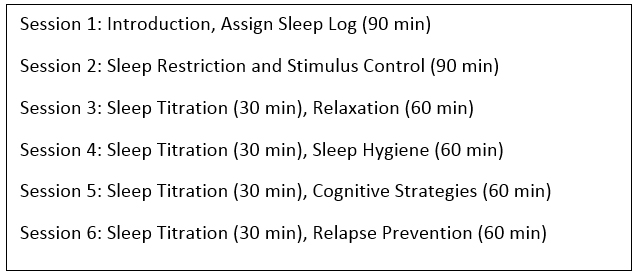

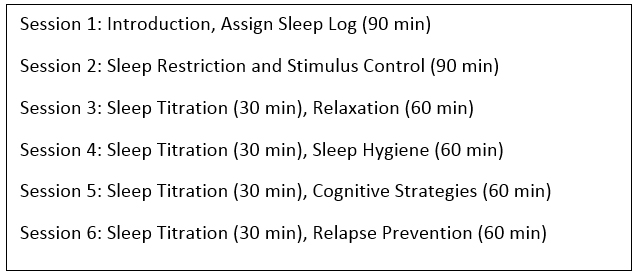

The main components of group CBTI, as with individual CBTI are: sleep restriction, stimulus control, psychoeducation, cognitive strategies for dysfunctional sleep-related beliefs, and relaxation. For whichever group length you choose, these components should be included. As the behavioral components have a stronger impact in the short term, I personally recommend starting your group with an introductory session to meet each other, orient to the concept of CBTI such as the rationale and expected outcomes, and introduce the sleep log right away. That way, sleep restriction and stimulus control can be prescribed at session two, and the remainder of group sessions can allow for time to review the sleep log at the beginning of each session to adjust the sleep schedule as needed, reinforce and problem solve sleep restriction and stimulus control. In these later sessions, the facilitator can then introduce or expand on other techniques as needed. Thus, a sample six session group structure might look like this, where “sleep titration” refers to using the sleep log to adjust the patient’s sleep schedule as indicated:

In fact, one of my favorite aspects of group CBTI is that time spent as a group at the beginning of each session reviewing each other’s sleep logs; group members often encourage each other to stick with the protocol and help find ways to boost adherence to sleep restriction and stimulus control. Koffel and colleagues (2015) similarly cite the benefit of social support inherent in group CBTI “at a time when patients are being asked to make challenging behavioral changes.”

I came up with the sample group CBTI structure above in the moment. Although as you can see you do not need to have a manual to set up a group, it can be helpful to have that guidance. If you have attended one of our workshops, you can check out our group CBTI resources on our Provider Portal that includes a suggested six-session manual and an introductory set of slides for session one. I’ll put in another plug to consider attending one of our workshops if you haven’t already, which gives you access to our provider portal and consultation, among other resources.

In summary, CBTI groups can be an effective, efficient way to deliver an evidence-based treatment for insomnia, especially when you have a high rate of sleep problems in your population. Providers who have training in individual CBTI will likely feel comfortable facilitating a group, as they rely on the same components. As with individual CBTI, the format is flexible in many ways, so it can be readily tailored to the specific needs of your clinic and your patients.

I hope you now feel excited about starting up a CBTI group! There are several keys to setting your group up for success, which include appropriate referral source and screening, size, logistics, etc. In Part 2 of this blog, we will share these tips as well as some case examples. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your questions and experiences below.

Diana C. Dolan, Ph.D., CBSM is a clinical psychologist serving as an evidence-based psychotherapy trainer with the Center for Deployment Psychology at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. In this capacity, she develops and presents trainings on a variety of EBPs and deployment-related topics, and provides consultation services.

References:

Edinger, J.D., & Sampson, W.S. (2003). A primary care “friendly” cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy. Sleep 26 (2): 177-182.

Koffel, E.A., Koffel, J.B., Gehrman, P.R. (2015). A meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews 19: 6-16.

Trauer, J.M., Qian, M.Y., Doyle, J.S., Rajaratnam, S.M.W., & Cunnington, D. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine doi: 10.7326/M14-2841. [Epub ahead of print]

Recently, we at the Center for Deployment Psychology have been receiving a number of consultation requests regarding translating the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBTI) package to a group setting. If you have been thinking about starting a CBTI group, allow me to increase your motivation and give you some resources to get started.

Let’s start by addressing what is probably a primary concern we have as providers when considering a new treatment approach: is this treatment effective? If you have attended one of our CBTI workshops, you know that individual treatment has clearly and repeatedly been demonstrated to be effective (and if you have not, we encourage you to visit our Training page here and sign up for one!). A timely meta-analysis published earlier this year documents effectiveness for CBTI group outcomes as well (Koffel et al, 2015).

The sleep-related outcomes that we consider important in CBTI can be separated into two categories, sleep quantity and sleep quality. As you may be familiar, patients with insomnia may initially focus on sleep quantity when seeking treatment, but CBTI aims to improve quality first by consolidating the patient’s sleep time. Additionally, some studies have observed that there are secondary outcomes that improve in CBTI as well, such as mood, nightmares or even pain in patients with co-morbid medical conditions, despite the fact that these variables are not targeted by CBTI.

One thing we know about CBTI is that outcomes are not only positive immediately post-treatment, but that they also persist long term, and in some cases, may even continue to improve over time after treatment discontinuation. Accordingly, in addition to reporting effect sizes for sleep quantity, sleep quality, and secondary outcomes, which included measures of mood and pain for the studies in which those were available, the group meta-analysis also included pre- to post-treatment as well as follow-up comparisons. Although follow-up differed by individual study, the range was 3 to 12 months.

The sample included eight RCTs with a total of 659 patients at baseline. Patients with co-morbid medical conditions were included in the sample, although unfortunately patients with co-morbid mental health conditions were not.

As you review the findings, keep in mind that when we evaluate effect sizes, a small effect size is generally considered to be around .2, a medium effect size around .5, and a large effect size .8 and higher. In looking at pre- to post-treatment change, and pre-treatment to follow-up change, the meta-analysis found the following effect sizes.

|

|

Group Pre- to Post-Treatment Effect Size |

Group Follow-Up Effect Size |

|

Sleep Efficiency (SE) |

1.13 |

.85 |

|

Sleep Onset Latency (SOL) |

.77 |

.60 |

|

Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO) |

.89 |

.63 |

|

Total Sleep Time (TST) |

.29 |

.60 |

|

Subjective Sleep Quality |

.85 |

1.26 |

|

Subjective Depression |

.26 |

.32 |

|

Subjective Pain |

.25 |

.41 |

I would like to point out that even while some outcomes had reduced effect sizes by the time of follow-up data collection, all effect sizes for the primary outcomes were still medium to large! That is, the majority of primary group outcomes were sustained over the long term, up to 12 months. Moreover, take a look at total sleep time (TST) and sleep quality-these effect sizes actually increased over the long term. Patients continue to improve the amount of sleep they get and how refreshed they feel after sleep once group CBTI has ended.

It gets better. Look at the last two rows, or the secondary outcomes. These were small at post-treatment, but increased by follow-up. While neither outcome reached a medium effect size, consider that this treatment was only designed to target insomnia. The improvement in mood and pain is an additional benefit. In my opinion, so far it seems there is nothing to be lost and a lot to gain from a trial of group CBTI. Hopefully, your motivation to start a CBTI group is increasing!

But wait, you may be thinking, “statistical improvement looks all well and good, but what does this mean for the patients?” Let’s break down these effect sizes into more real-life definitions. For example, the average baseline sleep efficiency (SE) went from 70 to 83% by post-treatment, and hovered at 80% at follow-up. The average sleep onset latency (SOL) went from 53 to 26 minutes by post-treatment, staying within the normal range at 30 minutes at follow-up. Similarly, the average wake after sleep onset (WASO) time went from 78 to 36 minutes by post-treatment, and then to 54 minutes at follow-up. Finally, the TST went from 340 to 359 minutes by post-treatment, then jumped to 374 minutes at follow-up. These numbers more concretely demonstrate that improvements after group CBTI are for the most part sustained, albeit without longer term (over a year) follow-up to conclusively confirm this. My interpretation is that as patients adjust their sleep schedules on their own sleep time continues to improve, but they may trade-off some time awake in bed in an effort to do so.

|

|

Overall Baseline |

Group Baseline |

Overall Post-Treatment Change |

Group Post-Treatment Change |

|

Sleep Efficiency (SE) |

71.8% |

69.51% |

9.91% |

13.81% |

|

Sleep Onset Latency (SOL) |

57.6 min |

52.75 min |

-19.03 min |

-27.25 min |

|

Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO) |

76 min |

77.54 min |

-26 min |

-41.38 min |

|

Total Sleep Time (TST) |

344.1 min |

340.18 min |

7.61 min |

18.80 min |

Of interest, I’ve created a table comparing the outcomes specifically from group CBTI to a meta-analysis of CBTI interventions in general, including both individual and group settings (Trauer et al, 2015), although I would strongly caution that as these data were not designed for direct comparison no firm conclusions should be made.

Note that I did not include the long term follow-up improvements, because the two meta-analyses calculated long term differently (eg, lumped as one large range vs broken down into several time intervals). While the overall CBTI meta-analysis includes group data which to some extent muddies the waters for interpretations, and while it is likely that groups tend to enroll lower complexity patients which potentially allows for greater range of improvement, we can certainly see the suggestion that group outcomes can be similarly effective to general CBTI outcomes including individual treatment.

Whew, that is a lot of data! If you have stuck with me thus far, I hope you are now convinced that group CBTI can be an effective treatment approach within the continuum of care for insomnia. Fortunately, in practice, group CBTI is comprised of a straightforward yet flexible structure that lends itself to implementation in a variety of settings. For example, in Koffel and colleagues’ group meta-analysis (2015), the number of group sessions ranged from 4 to 8, and the length of group sessions ranged from 60 to 120 minutes. While the study authors determined that a greater total number of minutes of treatment was related to greater improvement in sleep, other studies have shown that as few as two group sessions can improve sleep (Edinger & Sampson, 2003).

We recommend tailoring your group’s length and number of sessions to your clinic’s needs. In a primary care setting, two sessions may be more feasible, whereas in a high-acuity or inpatient setting, six to eight sessions offers more opportunity to address any challenges that may arise. In a military treatment facility (MTF) where classes may be offered on a monthly basis, a four-session approach may offer a good fit. Still other clinics may consider an open-format continuous CBTI group.

The main components of group CBTI, as with individual CBTI are: sleep restriction, stimulus control, psychoeducation, cognitive strategies for dysfunctional sleep-related beliefs, and relaxation. For whichever group length you choose, these components should be included. As the behavioral components have a stronger impact in the short term, I personally recommend starting your group with an introductory session to meet each other, orient to the concept of CBTI such as the rationale and expected outcomes, and introduce the sleep log right away. That way, sleep restriction and stimulus control can be prescribed at session two, and the remainder of group sessions can allow for time to review the sleep log at the beginning of each session to adjust the sleep schedule as needed, reinforce and problem solve sleep restriction and stimulus control. In these later sessions, the facilitator can then introduce or expand on other techniques as needed. Thus, a sample six session group structure might look like this, where “sleep titration” refers to using the sleep log to adjust the patient’s sleep schedule as indicated:

In fact, one of my favorite aspects of group CBTI is that time spent as a group at the beginning of each session reviewing each other’s sleep logs; group members often encourage each other to stick with the protocol and help find ways to boost adherence to sleep restriction and stimulus control. Koffel and colleagues (2015) similarly cite the benefit of social support inherent in group CBTI “at a time when patients are being asked to make challenging behavioral changes.”

I came up with the sample group CBTI structure above in the moment. Although as you can see you do not need to have a manual to set up a group, it can be helpful to have that guidance. If you have attended one of our workshops, you can check out our group CBTI resources on our Provider Portal that includes a suggested six-session manual and an introductory set of slides for session one. I’ll put in another plug to consider attending one of our workshops if you haven’t already, which gives you access to our provider portal and consultation, among other resources.

In summary, CBTI groups can be an effective, efficient way to deliver an evidence-based treatment for insomnia, especially when you have a high rate of sleep problems in your population. Providers who have training in individual CBTI will likely feel comfortable facilitating a group, as they rely on the same components. As with individual CBTI, the format is flexible in many ways, so it can be readily tailored to the specific needs of your clinic and your patients.

I hope you now feel excited about starting up a CBTI group! There are several keys to setting your group up for success, which include appropriate referral source and screening, size, logistics, etc. In Part 2 of this blog, we will share these tips as well as some case examples. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your questions and experiences below.

Diana C. Dolan, Ph.D., CBSM is a clinical psychologist serving as an evidence-based psychotherapy trainer with the Center for Deployment Psychology at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. In this capacity, she develops and presents trainings on a variety of EBPs and deployment-related topics, and provides consultation services.

References:

Edinger, J.D., & Sampson, W.S. (2003). A primary care “friendly” cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy. Sleep 26 (2): 177-182.

Koffel, E.A., Koffel, J.B., Gehrman, P.R. (2015). A meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews 19: 6-16.

Trauer, J.M., Qian, M.Y., Doyle, J.S., Rajaratnam, S.M.W., & Cunnington, D. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine doi: 10.7326/M14-2841. [Epub ahead of print]