Guest Perspective: Recommendations on How to Best Characterize and Document Suicide Risk

Editor’s Note: As part of the Center for Deployment Psychology’s ongoing mission to provide high-quality education on military- and deployment-related psychology, we are proud to present our latest “Guest Perspective.” Every Tuesday, we will be presenting blogs by esteemed guests and subject matter experts from outside the CDP. This allows us to offer more insight and opinions on a variety of topics of interest to behavioral health providers.

As these blog entries are written by outside authors, one important disclaimer: all of the opinions and ideas expressed in them are strictly those of the author alone and should not be taken as those of the CDP, Uniformed University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), or the Department of Defense (DoD).

That being said, we’re very happy to offer a platform where we can feature these individuals and the information they have to share. We’d like to make this an ongoing dialogue. If you have questions, remarks, or would like more information on a topic, please feel free to leave comments below or on our Facebook page, and we’ll pass them along to the author.

By Marjan G. Holloway, Ph.D., Major Matthew Nielsen, Psy.D., Lt Col Kathleen Crimmins, Ph.D., and Laura L. Neely, Psy.D.

Guest Columnist

As educators in the field of suicidology, we have often trained and supervised providers in the conduct of suicide risk assessments. In general, we have noted that while providers are becoming more knowledgeable about how to perform a suicide risk assessment, they continue to experience challenges in how to best communicate about suicide risk. Based on our experiences, we would like to provide you with some practical recommendations when completing clinical documentation and when consulting with colleagues.

Air Force Guide for Suicide Risk Assessment, Management, and Treatment

Appendices for Air Force Guide for Suicide Risk Assessment, Management, and Treatment

Function of Suicide Risk Assessment

A suicide risk assessment, when done correctly, can generate useful information for assessing the imminence of suicide risk. Such an assessment allows for the monitoring of risk at the time of the evaluation and over time. Additionally, the information gained through a suicide risk assessment serves as the foundation for subsequent suicide risk management and treatment. Finally, a suicide risk assessment can serve the function of de-escalating risk simply by having the patient feel more socially connected, understood, and hopeful about treatment options.

Sources of Information to Determine Suicide Risk

We all know that a comprehensive suicide risk assessment is based on a solid understanding of all factors contributing to a patient’s suicide ideation and/or behavior. Three sources of information are often used to determine risk: (1) clinical interview with the patient where he or she is asked direct questions about past and current suicide thoughts, intent, and plan, as well as risk and protective factors; (2) psychometrically sound psychological measures (e.g., self-report and/or clinician administered) given to the patient to directly assess for suicide risk; and (3) collateral data on observed warning signs (e.g., from military unit, peers, medical records, and/or family environment if available and with the proper releases obtained [as needed]).

Suicide Risk Level Determination

Once an evaluation has been conducted, one of the most important elements of documentation is to characterize suicide risk level. Such a risk level is determined based on your clinical interview, collateral data collected, and clinical judgment at the time of the evaluation. Overall, you are required to provide clear evidence that you reasonably and thoroughly assessed suicide risk, and how this assessment informed your decisions.

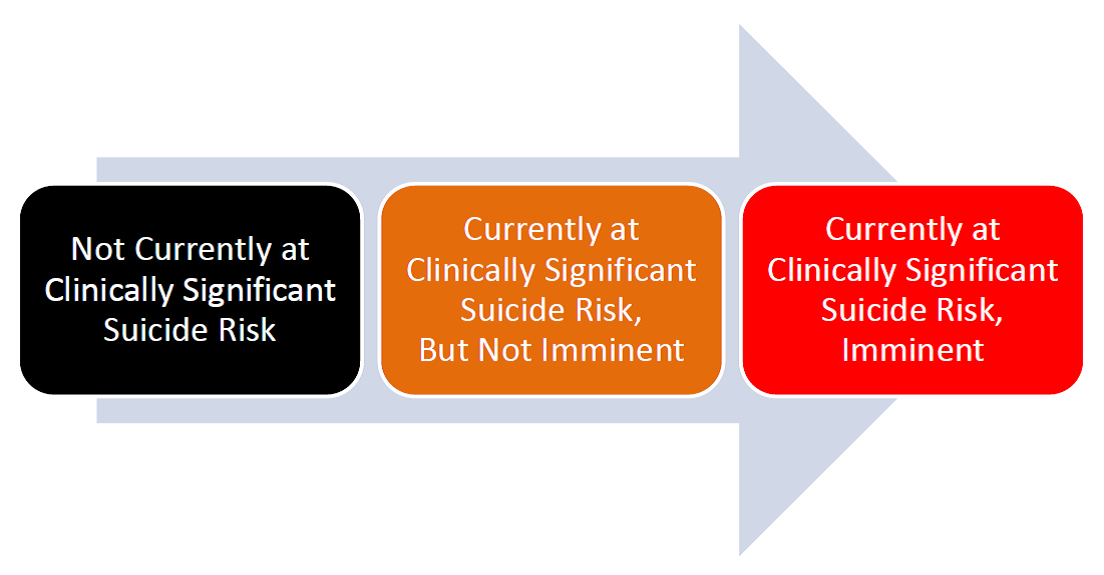

We have observed that many providers struggle with how to best characterize their suicide risk determination. Describing a patient’s suicide risk as mild, moderate, and/or severe, in our opinion, is very problematic as every provider may have a different perspective on what truly constitutes mild-moderate-severe suicide risk and therefore, these terms leave much room for ambiguity. Furthermore, in the field of suicidology, we continue to lack a consistent system of risk level classification.

We recommend that providers use the three suicide risk categories, as noted below in Figure 1, when documenting their risk severity determination: 1) Not Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, 2) Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, But Not Imminent, or 3) Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, Imminent. Please note that the suicide risk of any given patient may change (decrease or increase) upon departure from the mental health appointment, depending on a number of biopsychosocial factors; therefore, all three risk levels highlight that the determination has been made at the time of the evaluation (hence the use of the term, currently).

Figure 1. Suicide Risk Levels at Time of Evaluation

Based on your suicide risk assessment, we recommend that you first make the determination of whether or not the patient is currently at clinically significant suicide risk. Once you have made this determination, you subsequently make a decision about whether or not this observed risk is imminent. In order to determine the imminence of suicide risk, use clinical judgment, consult with peers, collect collateral information as needed, and consider all clinical and assessment data. Think about what elevates or lowers someone's risk for suicide, particularly your patient’s risk. There is currently no accepted standard definition of “imminent risk” – in general, an imminent event refers to an event soon to happen, but as we all know, soon is a relative term. Note that a patient at imminent risk will almost always be recommended, or at times required, for inpatient care.

Case Example of Suicide Risk Level Determination

SSgt Williams has been seeing Dr. Jones for one month for marital problems. During previous sessions, SSgt Williams disclosed that he has experienced suicidal ideation (SI) with the plan of shooting himself, but he denied intent and has some strong protective factors. Dr. Jones and SSgt Williams completed a collaborative Safety Plan, and, given the warning signs of current SI and plan, agreed to take the protective measure of giving his firearms to a friend temporarily. Dr. Jones has documented SSgt Williams’ risk level during previous sessions as “Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, But Not Imminent.” During today’s session, SSgt Williams revealed that his wife has asked for a divorce and moved out of the house. SSgt Williams is no longer future oriented and has a high degree of hopelessness. He stated, “If I had my guns I would kill myself. There is no reason to live anymore. If my friend won’t give me my guns back, I am sure I can get one at the store.” Dr. Jones elevated SSgt Williams’ risk level to “Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, Imminent” and arranged for transportation to an Emergency Department for further risk evaluation and possible inpatient hospitalization. Dr. Jones was sure to document in the clinical record all activities and decision-making processes for the clinical management of his at-risk patient, including status of elevated risk indicators and his rationale for transferring to an Emergency Department.

Documentation of Suicide Risk Assessment

Timely and effective documentation pertaining to your work with a suicidal patient is one of the most essential components of your job as a provider. When documenting, we recommend that you use a thorough, methodical approach to gathering, reviewing, and recording information. Clinical records are most complete when they document not only the initial risk assessment procedures and associated data, but also all activities and decision-making processes for the clinical management of the at-risk individual, such as your rationale for limiting access to lethal means and/or breaking confidentiality to communicate with command.

In general, intake documentation must be comprehensive, detailing at a minimum all risk and protective factors, history of suicide-related ideation and behaviors, and current levels of suicide ideation, planning, and intent. Standardized assessment instruments (e.g., Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale), and/or other psychometrically valid measures can provide a systematic means for documenting evidence for your risk screening, assessment, and subsequently planned interventions.

Follow-up entries can be much briefer; make sure to document status of elevated risk indicators (e.g., hopelessness, recent discharge from inpatient psychiatric care) until these risks have been resolved.

Documentation Checklist

At a minimum, include the following in your documentation:

- Methods of Suicide Risk Assessment

- Your Clinical Observations; Relevant Mental Status Information

- Brief Evaluation Summary

- Warning Signs; Risk Indicators; Access to Lethal Means

- Protective Factors

- Collateral Sources Used & Relevant Information Obtained

- Specific Assessment Data to Support Risk Determination

- Rationale for Actions Taken and Not Taken

- Provision of Military Crisis Line 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

- Implementation of Safety Plan (If Applicable)

Additional Recommendations on Documentation

Suicide Nomenclature

Pay close attention to language used to describe suicide-related information. Be knowledgeable of the Department of Defense (DoD) and Veterans Affairs (VA) suicide nomenclature. In an effort to provide consistency and clarity on suicide terminology, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (DoD, 2011) has mandated that all branches of the military adopt the Self-Directed Violence Classification System (SDVCS) developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for “future data collection, reporting, and/or system-wide comparisons” between the DoD and the VA. In the SDVCS, the two main types of events are thoughts and behaviors. Subtypes of thoughts are non-suicidal self-directed violence ideation and suicidal ideation. Behavior subtypes include preparatory behaviors, non-suicidal self-directed violence, undetermined self-directed violence, and suicidal self-directed violence. Each behavior subtype is further subdivided into terms, which are modified by intent, presence of injury, and interruption by self or other. A VA web page provides resources for training on the SDVCS.

Discrepancies in Patient’s Reporting of Suicidality

Document any discrepancies between a patient’s written and verbal statements, and how these were reconciled. Be sure to also document any discrepancies noted between a patient’s statements and the medical record.

Evidence-Based Treatment

Document use of evidence-informed as well as evidence-based treatment strategies specifically targeting suicide-related ideation and behaviors (e.g., Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Suicide Prevention, Safety Planning Intervention).

Medical Compliance and Engagement

For all patients, regardless of risk level at the time of evaluation, document missed sessions, dropping out of treatment prematurely, medication non-compliance, and/or other instances indicative of poor treatment engagement. Be sure to also document any attempts to contact or re-engage in therapy by you or the patient.

Coordination of Care

Document and share any significant changes in the risk status, treatment plan, or precautionary measures with the patient’s primary care manager or designee, the on-call mental-health provider, emergency department, and command immediately, and document date and time of this communication. Ensure that confidentiality is maximized and that you have obtained written authorization for “Release of Information” in cases where suicide risk is not recognized as imminent.

Consultation

Consult professional peers regularly regarding clinical work with suicidal patients and document the consultation. Make sure to document name and credentials of those you have consulted, the specific issues discussed, and the clinical decisions made as a result.

Clinical Challenges

Keep in mind that in certain situations, a risk indicator may be persistent and chronic. For instance, a patient may experience chronic suicide ideation during the entire outpatient care process. In these situations, use your clinical judgment and document reasons why risk status remains the same or is more or less elevated. For instance, if religious beliefs serve as a protective factor for this particular patient and there is an indication by the patient that despite the chronic suicide ideation, he would not act on suicidal self-inflicted injury due to involvement with his church, perceived social support, and beliefs in respecting one’s body, make sure to document your perspective on risk based on the weighing of risk and protective factors.

Note: This blog entry is based on recommendations provided in the 2014 Air Force Guide for Suicide Risk Assessment, Management, and Treatment and Appendices. These documents were prepared by the Laboratory for the Treatment of Suicide-Related Ideation and Behavior at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences under the direction of Dr. Marjan G. Holloway. Major Matthew Nielsen, formerly the Chief of Behavioral Health Optimization Program, Lieutenant Colonel Kathleen Crimmins, formerly the Air Force Suicide Prevention Program Manager, and Dr. Patricia Spangler (Postdoctoral Fellow) provided editorial assistance, made written contributions, and advised on content. Over twenty military providers in positions of leadership served as reviewers for the Guide.

Biographies of CDP Blog Contributors

Marjan G. Holloway,Ph.D. is a licensed Maryland Psychologist, and an Associate Professor of Medical & Clinical Psychology as well as Psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), Bethesda, MD. Her Laboratory for the Treatment of Suicide-Related Ideation and Behavior focuses on programmatic research on psychotherapy approaches to suicide prevention for military personnel, family members, and Veterans.

Maj Matthew Nielsen, Psy.D. ABPP is a licensed and board certified psychologist in the United States Air Force. He is currently a student at the Air Command and Staff College at Air University at Maxwell, Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama. Prior to this assignment, he worked in the Mental Health Branch at the Air Force Medical Operation Agency in San Antonio, Texas and led the Air Force's implementation of primary care behavioral health, mental health business practices, and the Air Force Guide for Suicide Risk Assessment, Management, and Treatment.

Laura L. Neely, Psy.D. is a licensed Maryland Psychologist, an Assistant Professor of Medical & Clinical Psychology at USUHS, and the Associate Director of the Laboratory for the Treatment of Suicide-Related Ideation and Behavior. Her areas of specialty include cognitive behavior therapy, suicide prevention, and psychiatric inpatient care.

Editor’s Note: As part of the Center for Deployment Psychology’s ongoing mission to provide high-quality education on military- and deployment-related psychology, we are proud to present our latest “Guest Perspective.” Every Tuesday, we will be presenting blogs by esteemed guests and subject matter experts from outside the CDP. This allows us to offer more insight and opinions on a variety of topics of interest to behavioral health providers.

As these blog entries are written by outside authors, one important disclaimer: all of the opinions and ideas expressed in them are strictly those of the author alone and should not be taken as those of the CDP, Uniformed University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), or the Department of Defense (DoD).

That being said, we’re very happy to offer a platform where we can feature these individuals and the information they have to share. We’d like to make this an ongoing dialogue. If you have questions, remarks, or would like more information on a topic, please feel free to leave comments below or on our Facebook page, and we’ll pass them along to the author.

By Marjan G. Holloway, Ph.D., Major Matthew Nielsen, Psy.D., Lt Col Kathleen Crimmins, Ph.D., and Laura L. Neely, Psy.D.

Guest Columnist

As educators in the field of suicidology, we have often trained and supervised providers in the conduct of suicide risk assessments. In general, we have noted that while providers are becoming more knowledgeable about how to perform a suicide risk assessment, they continue to experience challenges in how to best communicate about suicide risk. Based on our experiences, we would like to provide you with some practical recommendations when completing clinical documentation and when consulting with colleagues.

Air Force Guide for Suicide Risk Assessment, Management, and Treatment

Appendices for Air Force Guide for Suicide Risk Assessment, Management, and Treatment

Function of Suicide Risk Assessment

A suicide risk assessment, when done correctly, can generate useful information for assessing the imminence of suicide risk. Such an assessment allows for the monitoring of risk at the time of the evaluation and over time. Additionally, the information gained through a suicide risk assessment serves as the foundation for subsequent suicide risk management and treatment. Finally, a suicide risk assessment can serve the function of de-escalating risk simply by having the patient feel more socially connected, understood, and hopeful about treatment options.

Sources of Information to Determine Suicide Risk

We all know that a comprehensive suicide risk assessment is based on a solid understanding of all factors contributing to a patient’s suicide ideation and/or behavior. Three sources of information are often used to determine risk: (1) clinical interview with the patient where he or she is asked direct questions about past and current suicide thoughts, intent, and plan, as well as risk and protective factors; (2) psychometrically sound psychological measures (e.g., self-report and/or clinician administered) given to the patient to directly assess for suicide risk; and (3) collateral data on observed warning signs (e.g., from military unit, peers, medical records, and/or family environment if available and with the proper releases obtained [as needed]).

Suicide Risk Level Determination

Once an evaluation has been conducted, one of the most important elements of documentation is to characterize suicide risk level. Such a risk level is determined based on your clinical interview, collateral data collected, and clinical judgment at the time of the evaluation. Overall, you are required to provide clear evidence that you reasonably and thoroughly assessed suicide risk, and how this assessment informed your decisions.

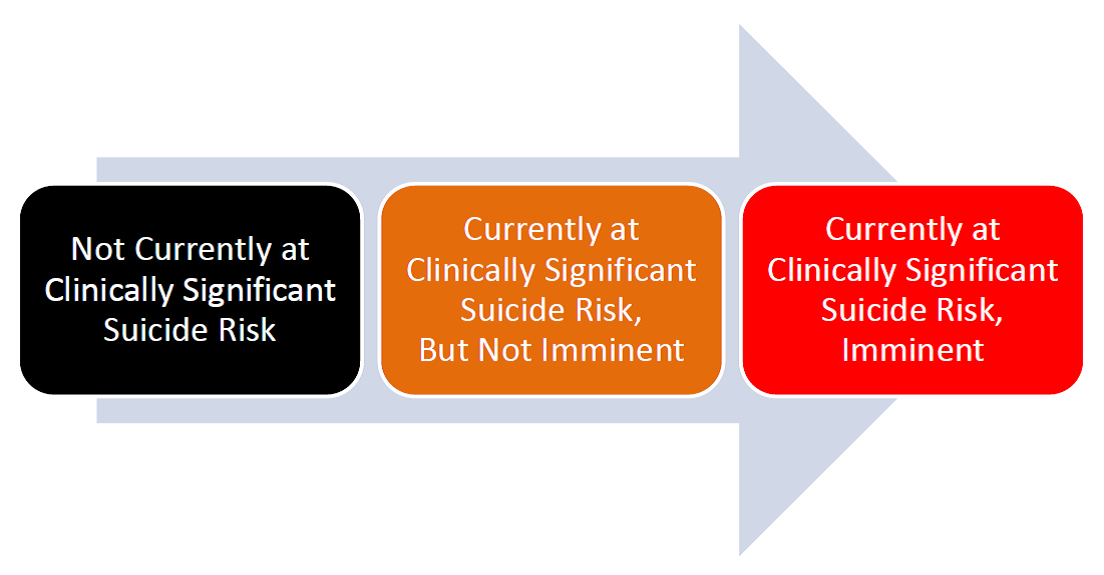

We have observed that many providers struggle with how to best characterize their suicide risk determination. Describing a patient’s suicide risk as mild, moderate, and/or severe, in our opinion, is very problematic as every provider may have a different perspective on what truly constitutes mild-moderate-severe suicide risk and therefore, these terms leave much room for ambiguity. Furthermore, in the field of suicidology, we continue to lack a consistent system of risk level classification.

We recommend that providers use the three suicide risk categories, as noted below in Figure 1, when documenting their risk severity determination: 1) Not Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, 2) Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, But Not Imminent, or 3) Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, Imminent. Please note that the suicide risk of any given patient may change (decrease or increase) upon departure from the mental health appointment, depending on a number of biopsychosocial factors; therefore, all three risk levels highlight that the determination has been made at the time of the evaluation (hence the use of the term, currently).

Figure 1. Suicide Risk Levels at Time of Evaluation

Based on your suicide risk assessment, we recommend that you first make the determination of whether or not the patient is currently at clinically significant suicide risk. Once you have made this determination, you subsequently make a decision about whether or not this observed risk is imminent. In order to determine the imminence of suicide risk, use clinical judgment, consult with peers, collect collateral information as needed, and consider all clinical and assessment data. Think about what elevates or lowers someone's risk for suicide, particularly your patient’s risk. There is currently no accepted standard definition of “imminent risk” – in general, an imminent event refers to an event soon to happen, but as we all know, soon is a relative term. Note that a patient at imminent risk will almost always be recommended, or at times required, for inpatient care.

Case Example of Suicide Risk Level Determination

SSgt Williams has been seeing Dr. Jones for one month for marital problems. During previous sessions, SSgt Williams disclosed that he has experienced suicidal ideation (SI) with the plan of shooting himself, but he denied intent and has some strong protective factors. Dr. Jones and SSgt Williams completed a collaborative Safety Plan, and, given the warning signs of current SI and plan, agreed to take the protective measure of giving his firearms to a friend temporarily. Dr. Jones has documented SSgt Williams’ risk level during previous sessions as “Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, But Not Imminent.” During today’s session, SSgt Williams revealed that his wife has asked for a divorce and moved out of the house. SSgt Williams is no longer future oriented and has a high degree of hopelessness. He stated, “If I had my guns I would kill myself. There is no reason to live anymore. If my friend won’t give me my guns back, I am sure I can get one at the store.” Dr. Jones elevated SSgt Williams’ risk level to “Currently at Clinically Significant Suicide Risk, Imminent” and arranged for transportation to an Emergency Department for further risk evaluation and possible inpatient hospitalization. Dr. Jones was sure to document in the clinical record all activities and decision-making processes for the clinical management of his at-risk patient, including status of elevated risk indicators and his rationale for transferring to an Emergency Department.

Documentation of Suicide Risk Assessment

Timely and effective documentation pertaining to your work with a suicidal patient is one of the most essential components of your job as a provider. When documenting, we recommend that you use a thorough, methodical approach to gathering, reviewing, and recording information. Clinical records are most complete when they document not only the initial risk assessment procedures and associated data, but also all activities and decision-making processes for the clinical management of the at-risk individual, such as your rationale for limiting access to lethal means and/or breaking confidentiality to communicate with command.

In general, intake documentation must be comprehensive, detailing at a minimum all risk and protective factors, history of suicide-related ideation and behaviors, and current levels of suicide ideation, planning, and intent. Standardized assessment instruments (e.g., Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale), and/or other psychometrically valid measures can provide a systematic means for documenting evidence for your risk screening, assessment, and subsequently planned interventions.

Follow-up entries can be much briefer; make sure to document status of elevated risk indicators (e.g., hopelessness, recent discharge from inpatient psychiatric care) until these risks have been resolved.

Documentation Checklist

At a minimum, include the following in your documentation:

- Methods of Suicide Risk Assessment

- Your Clinical Observations; Relevant Mental Status Information

- Brief Evaluation Summary

- Warning Signs; Risk Indicators; Access to Lethal Means

- Protective Factors

- Collateral Sources Used & Relevant Information Obtained

- Specific Assessment Data to Support Risk Determination

- Rationale for Actions Taken and Not Taken

- Provision of Military Crisis Line 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

- Implementation of Safety Plan (If Applicable)

Additional Recommendations on Documentation

Suicide Nomenclature

Pay close attention to language used to describe suicide-related information. Be knowledgeable of the Department of Defense (DoD) and Veterans Affairs (VA) suicide nomenclature. In an effort to provide consistency and clarity on suicide terminology, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (DoD, 2011) has mandated that all branches of the military adopt the Self-Directed Violence Classification System (SDVCS) developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for “future data collection, reporting, and/or system-wide comparisons” between the DoD and the VA. In the SDVCS, the two main types of events are thoughts and behaviors. Subtypes of thoughts are non-suicidal self-directed violence ideation and suicidal ideation. Behavior subtypes include preparatory behaviors, non-suicidal self-directed violence, undetermined self-directed violence, and suicidal self-directed violence. Each behavior subtype is further subdivided into terms, which are modified by intent, presence of injury, and interruption by self or other. A VA web page provides resources for training on the SDVCS.

Discrepancies in Patient’s Reporting of Suicidality

Document any discrepancies between a patient’s written and verbal statements, and how these were reconciled. Be sure to also document any discrepancies noted between a patient’s statements and the medical record.

Evidence-Based Treatment

Document use of evidence-informed as well as evidence-based treatment strategies specifically targeting suicide-related ideation and behaviors (e.g., Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Suicide Prevention, Safety Planning Intervention).

Medical Compliance and Engagement

For all patients, regardless of risk level at the time of evaluation, document missed sessions, dropping out of treatment prematurely, medication non-compliance, and/or other instances indicative of poor treatment engagement. Be sure to also document any attempts to contact or re-engage in therapy by you or the patient.

Coordination of Care

Document and share any significant changes in the risk status, treatment plan, or precautionary measures with the patient’s primary care manager or designee, the on-call mental-health provider, emergency department, and command immediately, and document date and time of this communication. Ensure that confidentiality is maximized and that you have obtained written authorization for “Release of Information” in cases where suicide risk is not recognized as imminent.

Consultation

Consult professional peers regularly regarding clinical work with suicidal patients and document the consultation. Make sure to document name and credentials of those you have consulted, the specific issues discussed, and the clinical decisions made as a result.

Clinical Challenges

Keep in mind that in certain situations, a risk indicator may be persistent and chronic. For instance, a patient may experience chronic suicide ideation during the entire outpatient care process. In these situations, use your clinical judgment and document reasons why risk status remains the same or is more or less elevated. For instance, if religious beliefs serve as a protective factor for this particular patient and there is an indication by the patient that despite the chronic suicide ideation, he would not act on suicidal self-inflicted injury due to involvement with his church, perceived social support, and beliefs in respecting one’s body, make sure to document your perspective on risk based on the weighing of risk and protective factors.

Note: This blog entry is based on recommendations provided in the 2014 Air Force Guide for Suicide Risk Assessment, Management, and Treatment and Appendices. These documents were prepared by the Laboratory for the Treatment of Suicide-Related Ideation and Behavior at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences under the direction of Dr. Marjan G. Holloway. Major Matthew Nielsen, formerly the Chief of Behavioral Health Optimization Program, Lieutenant Colonel Kathleen Crimmins, formerly the Air Force Suicide Prevention Program Manager, and Dr. Patricia Spangler (Postdoctoral Fellow) provided editorial assistance, made written contributions, and advised on content. Over twenty military providers in positions of leadership served as reviewers for the Guide.

Biographies of CDP Blog Contributors

Marjan G. Holloway,Ph.D. is a licensed Maryland Psychologist, and an Associate Professor of Medical & Clinical Psychology as well as Psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), Bethesda, MD. Her Laboratory for the Treatment of Suicide-Related Ideation and Behavior focuses on programmatic research on psychotherapy approaches to suicide prevention for military personnel, family members, and Veterans.

Maj Matthew Nielsen, Psy.D. ABPP is a licensed and board certified psychologist in the United States Air Force. He is currently a student at the Air Command and Staff College at Air University at Maxwell, Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama. Prior to this assignment, he worked in the Mental Health Branch at the Air Force Medical Operation Agency in San Antonio, Texas and led the Air Force's implementation of primary care behavioral health, mental health business practices, and the Air Force Guide for Suicide Risk Assessment, Management, and Treatment.

Laura L. Neely, Psy.D. is a licensed Maryland Psychologist, an Assistant Professor of Medical & Clinical Psychology at USUHS, and the Associate Director of the Laboratory for the Treatment of Suicide-Related Ideation and Behavior. Her areas of specialty include cognitive behavior therapy, suicide prevention, and psychiatric inpatient care.