Staff Perspective: Four Questions to Ask About Complementary and Alternative Interventions for Mental Health Conditions

- Complementary and alternative medicine

- Adjunctive treatments

- Holistic interventions

- Integrative medicine

There are almost as many names for treatments that fall outside traditional Western medicine as there are examples of it: yoga, acupuncture, weighted blankets, herbal remedies, healing crystals, and animal-facilitated interventions, to name just a few. These interventions have become increasingly accessible and utilized by our patients. At every evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) workshop that I’ve taught recently, I’ve been asked at least once, “But what about St. John’s Wort/Tai Chi/binaural beats/meditation?” While interest in these interventions has grown, the science behind them is still cloudy, making it difficult to answer this question definitively. Rather than try to formulate a one-size-fits-all answer, I find it more helpful to consider the ways that the complementary intervention augments or contradicts the EBP for that condition. There are four questions that help me critically evaluate the suitability of these interventions for patients.

Note: for ease of discussion, I’ll use “complementary intervention” as an umbrella term for these interventions.

Four questions to ask about complementary interventions for mental health conditions:

1. WHY does it work?

Before we recommend using or avoiding a particular intervention, it is important to consider how and why the intervention works. We could simply repeat the rationale provided by the proponent for the intervention, but it seems unethical to not develop a more thorough conceptualization about why it may (or may not) work for our specific patient. For instance, I’m a big fan of animal-assisted interventions. If I was running for public office, my slogan would be “Lefkowitz 2020: Puppies and Kittens for Everyone!” I’m automatically happier when my cat rubs against my legs and there are plenty of explanations for why that might be. One oft-repeated rationale is “pets provide unconditional positive regard.” Although this is likely true, that probably just means we should all have a pet (please refer back to my winning campaign slogan). If I am to actively recommend an animal-assisted intervention, I need a more sophisticated rationale for why and how a specific client will benefit. How can I harness that unconditional positive regard to help a client with major depression, for example? Perhaps the patient’s dog greeting him at the door with a wagging tail can provide some evidence against a negative core belief, such as “I’m not likeable.” The mechanism of action here isn’t just the wagging tail, but rather what that greeting means to the client and how it can help restructure negative cognitions.

Of course, it’s not enough to just be a passive recipient of information, even when I’m the one spewing it. As clinicians, we need to thoughtfully consider where the evidence is coming from and how legitimate it is, which brings us to question #2...

2. What is the quality of evidence being cited?

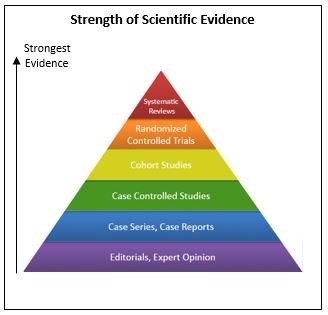

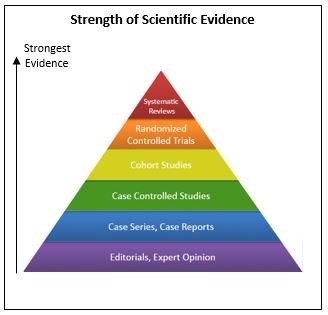

While proponents of specific interventions are typically eager to provide evidence to support their claims, as clinicians we need to consider the soundness of that evidence. The image below illustrates the various levels of scientific rigor underlying data, with editorials and expert opinions having the lowest levels of rigor and systematic reviews having the highest. In this context, even anecdotal information is useful. Knowing that several of my patients have responded well to a particular smart phone app or a specific yoga class suggests that those strategies may help the subset of patients that I work with. But that anecdotal information is not strong enough to make me recommend those strategies before or instead of an EBP that is backed by years of rigorous research. In fact, when considering levels of evidence, anecdotal examples probably fit in best with “case reports;” while case reports and anecdotal evidence are important in that they elucidate promising options for further exploration, they are very low on the scale of scientific strength. Unfortunately, most of the data supporting complementary interventions are case series or case reports, while systematic reviews conclude that there is no difference between most complementary interventions and placebo and/or the research methodology of individual studies are flawed or biased*. We simply don’t have any evidence to suggest that these interventions can or should replace EBPs, which are supported by randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews.

While proponents of specific interventions are typically eager to provide evidence to support their claims, as clinicians we need to consider the soundness of that evidence. The image below illustrates the various levels of scientific rigor underlying data, with editorials and expert opinions having the lowest levels of rigor and systematic reviews having the highest. In this context, even anecdotal information is useful. Knowing that several of my patients have responded well to a particular smart phone app or a specific yoga class suggests that those strategies may help the subset of patients that I work with. But that anecdotal information is not strong enough to make me recommend those strategies before or instead of an EBP that is backed by years of rigorous research. In fact, when considering levels of evidence, anecdotal examples probably fit in best with “case reports;” while case reports and anecdotal evidence are important in that they elucidate promising options for further exploration, they are very low on the scale of scientific strength. Unfortunately, most of the data supporting complementary interventions are case series or case reports, while systematic reviews conclude that there is no difference between most complementary interventions and placebo and/or the research methodology of individual studies are flawed or biased*. We simply don’t have any evidence to suggest that these interventions can or should replace EBPs, which are supported by randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews.

3. Does it complement evidence-based treatments for this condition?

While the research literature does not support the use of complementary interventions instead of EBPs, many interventions are supported as adjuncts to treatment. For example, there is evidence that meditation can improve symptoms of insomnia, although it is not a replacement for the gold-standard treatment, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI). In deciding how to support a client practicing meditation while engaged in CBTI, I might ask myself whether meditation complements the core components of CBTI. A course of CBTI typically includes the behavioral techniques of stimulus control and sleep restriction, cognitive therapy for negative sleep-related beliefs, a relaxation component and a review of sleep hygiene. In this case, meditation fits in nicely with the relaxation component. So if a client expressed interest in meditation, I could easily incorporate that as the relaxation practice as opposed to my usual approach (progressive muscle relaxation or guided imagery). I could make the same argument for other complementary interventions for sleep such as drinking chamomile tea or practicing biofeedback.

4. Is it inconsistent with EBPs for this condition?

While it’s been established that complementary interventions can be, well, complementary to EBPs, it’s important to be aware that they can also inadvertently undermine the goals or mechanisms of EBPs. Again using the example of meditation, what if another client wanted to practice meditation while simultaneously engaging in Prolonged Exposure (PE), an EBP for PTSD? At first glance, I might theorize that meditation helps to lower arousal, so of course it could help reduce PTSD symptoms. But when I consider the specific techniques and mechanisms of action of PE, it becomes less clear. PE’s main techniques include imaginal exposure and in vivo exposure, both of which serve to activate anxiety and promote habituation. By repeatedly revisiting the trauma in session and listening to recordings at home, the client stops avoiding anxiety related to their trauma memory, learns that anxiety is not dangerous, and that it will naturally decrease with time. During in vivo exposure, the client learns similar lessons regarding real-life scenarios that the client has been avoiding because it reminds them about the trauma or makes them feel vulnerable, such as watching combat movies or sitting with one’s back to a crowd. During both types of exposure, the client is actively tracking the severity of their anxiety. From this perspective, I see potential conflicts with meditation: I want the client to actively engage with anxiety during PE and learn that they will naturally habituate to it over time. Practicing meditation while listening to a recording of an imaginal exposure or during an in vivo exposure could prevent or diminish that engagement and also undermines the lessons that anxiety does not need to be avoided and that it will decrease naturally without intervention. In these ways, meditation may be incompatible with PE and this needs to be discussed openly with the patient. At the very least, if my client is committed to practicing meditation, we’ll need to develop a specific plan about how to keep it from interfering with PE (for example, agreeing that the client will continue to practice meditation before bed, but not during or immediately after an exposure assignment).

In summary, it’s good to have a wide range of tools with which to help your patients. While I strongly advocate using EBPs whenever possible, I am well aware that engaging in these treatments often require a good deal of faith and delaying of gratification from patients. Oftentimes they want something that will make them feel better more quickly, and that’s a healthy, reasonable desire. Ultimately, that is how I understand the role that adjunctive treatments play in my practice. To use an analogy, illnesses such as major depression or PTSD are painful and require specific medical intervention, much like a stomach ulcer. If left untreated an ulcer can cause not only physical pain, but also functional impairment in terms of missed days of work and even social discomfort. Effective treatments exist (proton-pump inhibitors or antibiotics, for example), but may take several weeks to fully heal the ulcer. Antacids have no impact on the ulcer itself, but may provide temporary relief while the other treatments are administered. Would I eat antacid like candy if I had an ulcer while I waited for other treatments to take effect? Definitely. In the same way, I support my patients practicing yoga or keeping energy crystals on their nightstand if it offers temporary relief, but I am clear that I consider them to be adjunctive to EBPs, rather than as a replacement.

The opinions in CDP Staff Perspective blogs are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science or the Department of Defense.

Carin Lefkowitz, Psy.D., is a clinical psychologist and Military Behavioral Health Psychologist at the Center for Deployment Psychology at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, MD.

References:

Asher, G., Gartlehner, G., Gaynes, B., Amick, H., Forneris, C. ….. & Lohr, K. (2017). Comparative benefits and harms of complementary and alternative medicine therapies for initial treatment of major depressive disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 23(12). http://doi.org.lrc1.usuhs.edu/10.1089/acm.2016.0261

Malaktaris, A. & Lang, A. (2018, August 30). Complementary and integrative health approaches for PTSD. Psychiatric Times, 35(8). Retrieved from: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/special-reports/complementary-and-integrative-health-approaches-ptsd

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). (2014, April). Sleep disorders and complementary health approaches: What the science says. NCCIH Clinical Digest. Retrieved from: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/sleep-disorders-science

- Complementary and alternative medicine

- Adjunctive treatments

- Holistic interventions

- Integrative medicine

There are almost as many names for treatments that fall outside traditional Western medicine as there are examples of it: yoga, acupuncture, weighted blankets, herbal remedies, healing crystals, and animal-facilitated interventions, to name just a few. These interventions have become increasingly accessible and utilized by our patients. At every evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) workshop that I’ve taught recently, I’ve been asked at least once, “But what about St. John’s Wort/Tai Chi/binaural beats/meditation?” While interest in these interventions has grown, the science behind them is still cloudy, making it difficult to answer this question definitively. Rather than try to formulate a one-size-fits-all answer, I find it more helpful to consider the ways that the complementary intervention augments or contradicts the EBP for that condition. There are four questions that help me critically evaluate the suitability of these interventions for patients.

Note: for ease of discussion, I’ll use “complementary intervention” as an umbrella term for these interventions.

Four questions to ask about complementary interventions for mental health conditions:

1. WHY does it work?

Before we recommend using or avoiding a particular intervention, it is important to consider how and why the intervention works. We could simply repeat the rationale provided by the proponent for the intervention, but it seems unethical to not develop a more thorough conceptualization about why it may (or may not) work for our specific patient. For instance, I’m a big fan of animal-assisted interventions. If I was running for public office, my slogan would be “Lefkowitz 2020: Puppies and Kittens for Everyone!” I’m automatically happier when my cat rubs against my legs and there are plenty of explanations for why that might be. One oft-repeated rationale is “pets provide unconditional positive regard.” Although this is likely true, that probably just means we should all have a pet (please refer back to my winning campaign slogan). If I am to actively recommend an animal-assisted intervention, I need a more sophisticated rationale for why and how a specific client will benefit. How can I harness that unconditional positive regard to help a client with major depression, for example? Perhaps the patient’s dog greeting him at the door with a wagging tail can provide some evidence against a negative core belief, such as “I’m not likeable.” The mechanism of action here isn’t just the wagging tail, but rather what that greeting means to the client and how it can help restructure negative cognitions.

Of course, it’s not enough to just be a passive recipient of information, even when I’m the one spewing it. As clinicians, we need to thoughtfully consider where the evidence is coming from and how legitimate it is, which brings us to question #2...

2. What is the quality of evidence being cited?  While proponents of specific interventions are typically eager to provide evidence to support their claims, as clinicians we need to consider the soundness of that evidence. The image below illustrates the various levels of scientific rigor underlying data, with editorials and expert opinions having the lowest levels of rigor and systematic reviews having the highest. In this context, even anecdotal information is useful. Knowing that several of my patients have responded well to a particular smart phone app or a specific yoga class suggests that those strategies may help the subset of patients that I work with. But that anecdotal information is not strong enough to make me recommend those strategies before or instead of an EBP that is backed by years of rigorous research. In fact, when considering levels of evidence, anecdotal examples probably fit in best with “case reports;” while case reports and anecdotal evidence are important in that they elucidate promising options for further exploration, they are very low on the scale of scientific strength. Unfortunately, most of the data supporting complementary interventions are case series or case reports, while systematic reviews conclude that there is no difference between most complementary interventions and placebo and/or the research methodology of individual studies are flawed or biased*. We simply don’t have any evidence to suggest that these interventions can or should replace EBPs, which are supported by randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews.

While proponents of specific interventions are typically eager to provide evidence to support their claims, as clinicians we need to consider the soundness of that evidence. The image below illustrates the various levels of scientific rigor underlying data, with editorials and expert opinions having the lowest levels of rigor and systematic reviews having the highest. In this context, even anecdotal information is useful. Knowing that several of my patients have responded well to a particular smart phone app or a specific yoga class suggests that those strategies may help the subset of patients that I work with. But that anecdotal information is not strong enough to make me recommend those strategies before or instead of an EBP that is backed by years of rigorous research. In fact, when considering levels of evidence, anecdotal examples probably fit in best with “case reports;” while case reports and anecdotal evidence are important in that they elucidate promising options for further exploration, they are very low on the scale of scientific strength. Unfortunately, most of the data supporting complementary interventions are case series or case reports, while systematic reviews conclude that there is no difference between most complementary interventions and placebo and/or the research methodology of individual studies are flawed or biased*. We simply don’t have any evidence to suggest that these interventions can or should replace EBPs, which are supported by randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews.

3. Does it complement evidence-based treatments for this condition?

While the research literature does not support the use of complementary interventions instead of EBPs, many interventions are supported as adjuncts to treatment. For example, there is evidence that meditation can improve symptoms of insomnia, although it is not a replacement for the gold-standard treatment, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI). In deciding how to support a client practicing meditation while engaged in CBTI, I might ask myself whether meditation complements the core components of CBTI. A course of CBTI typically includes the behavioral techniques of stimulus control and sleep restriction, cognitive therapy for negative sleep-related beliefs, a relaxation component and a review of sleep hygiene. In this case, meditation fits in nicely with the relaxation component. So if a client expressed interest in meditation, I could easily incorporate that as the relaxation practice as opposed to my usual approach (progressive muscle relaxation or guided imagery). I could make the same argument for other complementary interventions for sleep such as drinking chamomile tea or practicing biofeedback.

4. Is it inconsistent with EBPs for this condition?

While it’s been established that complementary interventions can be, well, complementary to EBPs, it’s important to be aware that they can also inadvertently undermine the goals or mechanisms of EBPs. Again using the example of meditation, what if another client wanted to practice meditation while simultaneously engaging in Prolonged Exposure (PE), an EBP for PTSD? At first glance, I might theorize that meditation helps to lower arousal, so of course it could help reduce PTSD symptoms. But when I consider the specific techniques and mechanisms of action of PE, it becomes less clear. PE’s main techniques include imaginal exposure and in vivo exposure, both of which serve to activate anxiety and promote habituation. By repeatedly revisiting the trauma in session and listening to recordings at home, the client stops avoiding anxiety related to their trauma memory, learns that anxiety is not dangerous, and that it will naturally decrease with time. During in vivo exposure, the client learns similar lessons regarding real-life scenarios that the client has been avoiding because it reminds them about the trauma or makes them feel vulnerable, such as watching combat movies or sitting with one’s back to a crowd. During both types of exposure, the client is actively tracking the severity of their anxiety. From this perspective, I see potential conflicts with meditation: I want the client to actively engage with anxiety during PE and learn that they will naturally habituate to it over time. Practicing meditation while listening to a recording of an imaginal exposure or during an in vivo exposure could prevent or diminish that engagement and also undermines the lessons that anxiety does not need to be avoided and that it will decrease naturally without intervention. In these ways, meditation may be incompatible with PE and this needs to be discussed openly with the patient. At the very least, if my client is committed to practicing meditation, we’ll need to develop a specific plan about how to keep it from interfering with PE (for example, agreeing that the client will continue to practice meditation before bed, but not during or immediately after an exposure assignment).

In summary, it’s good to have a wide range of tools with which to help your patients. While I strongly advocate using EBPs whenever possible, I am well aware that engaging in these treatments often require a good deal of faith and delaying of gratification from patients. Oftentimes they want something that will make them feel better more quickly, and that’s a healthy, reasonable desire. Ultimately, that is how I understand the role that adjunctive treatments play in my practice. To use an analogy, illnesses such as major depression or PTSD are painful and require specific medical intervention, much like a stomach ulcer. If left untreated an ulcer can cause not only physical pain, but also functional impairment in terms of missed days of work and even social discomfort. Effective treatments exist (proton-pump inhibitors or antibiotics, for example), but may take several weeks to fully heal the ulcer. Antacids have no impact on the ulcer itself, but may provide temporary relief while the other treatments are administered. Would I eat antacid like candy if I had an ulcer while I waited for other treatments to take effect? Definitely. In the same way, I support my patients practicing yoga or keeping energy crystals on their nightstand if it offers temporary relief, but I am clear that I consider them to be adjunctive to EBPs, rather than as a replacement.

The opinions in CDP Staff Perspective blogs are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science or the Department of Defense.

Carin Lefkowitz, Psy.D., is a clinical psychologist and Military Behavioral Health Psychologist at the Center for Deployment Psychology at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, MD.

References:

Asher, G., Gartlehner, G., Gaynes, B., Amick, H., Forneris, C. ….. & Lohr, K. (2017). Comparative benefits and harms of complementary and alternative medicine therapies for initial treatment of major depressive disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 23(12). http://doi.org.lrc1.usuhs.edu/10.1089/acm.2016.0261

Malaktaris, A. & Lang, A. (2018, August 30). Complementary and integrative health approaches for PTSD. Psychiatric Times, 35(8). Retrieved from: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/special-reports/complementary-and-integrative-health-approaches-ptsd

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). (2014, April). Sleep disorders and complementary health approaches: What the science says. NCCIH Clinical Digest. Retrieved from: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/sleep-disorders-science