Staff Perspective: Telling About the Trauma

Previously, I wrote about why combat veterans hesitate to share details about their combat experiences. These insights could be adjusted to anyone who has experienced trauma. I’ve repeatedly had veterans, providers, and family members tell me this makes sense to them. However, understanding a hesitancy to share does not mean it is okay to tell loved ones absolutely nothing about what happened if someone is struggling with the aftermath of trauma. People have a right to their privacy and to keep certain information to themselves. Yet family and friends also have the right to know something about what is happening. So how do we help those with trauma feel more comfortable sharing their experiences with loved ones? What are the boundaries around what is told and what isn’t?

First, we need to distinguish between sharing about the trauma and sharing about the person’s trauma reactions. Symptoms, triggers, and what a person can do to help with them are not the same as telling someone the actual details of the trauma story. When someone asks for information, are they asking more for details on how they can assist in the moment or future, or about the past event itself? Emotions run high around trauma reactions, and it can be difficult in the moment to tell the difference. Learning how to really listen to the questions asked can be a way to feel more calm and in control of the situation. Often, if the person is asking a “what happened” question, it can be redirected to an “in the moment trigger” answer.

For example, if someone notices a trauma survivor is struggling after being triggered and asks if they are okay and want to talk about what happened, this could be interpreted as them asking for details of the trauma story, and indeed this could be what the person is asking for. But the trauma survivor can instead choose to answer by saying they have a trauma history and were triggered by whatever sound or thing it was. Then they can add what would help in the moment, such as they just need a few moments of quiet outside and it would be helpful for the person to be sure that no one bothers them, or runs interference by letting others who may have witnessed the event know that things are fine or make up a plausible story to cover for them. The idea is that usually a friend or bystander doesn’t need details of the trauma, but to feel they are helping the trauma survivor, so give them something that makes them feel helpful. It can be embarrassing for trauma survivors to have others witness their symptoms. But this happens. A way to handle the embarrassment is to maintain control of the information shared and what happens next.

Often, close friends and family don’t need details of the trauma story either. They may just need enough to have an idea of what happened and need more details on what symptoms the trauma survivor is going through and what they can do to best support the person. So think of this as learning how to discuss two distinct categories of trauma information – (1) the story details and (2) the trauma reaction and treatment details. For each of these, there will be boundaries about how much you give to whom. Trauma survivors never have to give all information to anyone, period. No one, no matter what they initially think, wants all the details. It isn’t healthy for either person. So how do you know how much to share? And just as critical, what don’t you share. Knowing this can make a person less concerned that they will say something by accident.

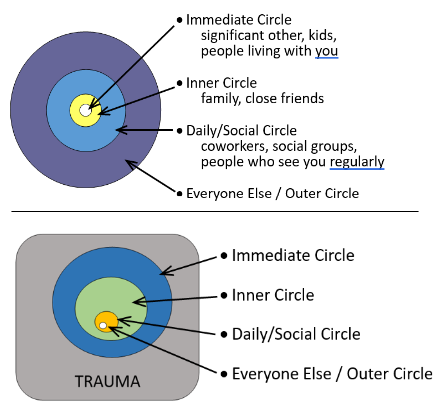

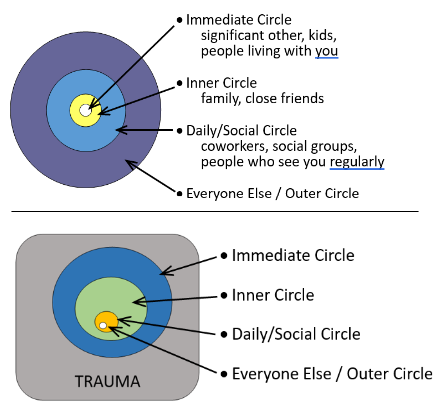

I like to have clients think of sharing information within circles of details. What they share depends on what circle a person is in. Usually by default, more of the trauma story details are shared with those closest to the individual with much less detail shared with people as they become more distant to the individual. Instead, the more distant individuals tend to get primarily trauma reaction and possibly no trauma story information. Visually, the circles of detail could look something like the bullseye seen here. Or below it, there is an inverse which visually depicts the group circles depending on how much trauma information they receive. While I’ve given labels to the circles, how a client divides things is up to them. The point is they have clear divisions between distinct groupings of people who get different levels of information.

individual with much less detail shared with people as they become more distant to the individual. Instead, the more distant individuals tend to get primarily trauma reaction and possibly no trauma story information. Visually, the circles of detail could look something like the bullseye seen here. Or below it, there is an inverse which visually depicts the group circles depending on how much trauma information they receive. While I’ve given labels to the circles, how a client divides things is up to them. The point is they have clear divisions between distinct groupings of people who get different levels of information.

The smallest group of individuals with the highest need to know is the Immediate Circle. These are the closest to the person such as a spouse or significant other and other individuals living within the home who will see the worst of what the person goes through. Because of what they will witness, they will need more information to understand and help calm their own anxiety. While deployed to a combat zone myself, I had to remind people that if they didn’t tell their loved ones any details, the only thing their families had to fill in the blanks were the things they saw on the news which was usually more alarming than reality. It is not a good idea to let people’s imaginations fill in the blanks because, even if the reality is bad, the known reality is almost always better than the unknown imagined.

That said, the details shared should never be everything. There will always be information held back which is too uncomfortable to give. It is crucial that a person defines what is important to share, what will not be shared, and then practices how to give the information in a way that relays what they want to say and with the amount of detail they want to give. Practice saying it out loud. This will build self-trust so when the time comes the desired boundaries will be set. A quick caveat about children who live in the home who are within this immediate circle. Children should not be told the same amount of detail as adults, ever. They should be told age-appropriate information and in a manner that does not frighten them about a parent’s ability to care for them. How and what to tell children should be discussed with significant others as well as child professionals as needed.

The next circle is the Inner Circle. These are still people who are very close to the trauma survivor such as immediate family and close friends. They are part of the close support system. However, they likely do not live in the same household. While it is still a good idea to tell these people details about the trauma story so their imaginations don’t get the better of them, they may not need the same details as the spouse or significant other. This is where it can get a bit strange – sometimes certain individuals in the inner circle will be privileged with more details to aspects of the story than the immediate circle. This is perfectly fine, although if this could cause friction with a spouse/significant other, how to normalize this with them is important. For example, perhaps a close friend has also experienced a traumatic event and the client feels more comfortable sharing certain details with them. Sometimes, certain individuals simply have the type of personality that makes sharing specific details easier. Whatever the reason, a client has the right to define specific individuals who are classified differently from others in terms of what information they are given. They can create completely unique circles for them that fall within and overlapping the inner and immediate circles.

Both the Immediate and Inner Circles involve a client’s closest friends, family, and immediate supports. Because of this, they need to have details about the client’s trauma reactions and what they can do to assist when needed. Consider what is likely to come up with the individuals and what they can realistically do to help.

The Daily Contact and Social Circle includes people who a person has regular contact with, but isn’t necessarily close with - casual friends, coworkers, etc. These aren’t going to be people someone calls in an emotional emergency unless absolutely no one else is available. These people know the trauma survivor well enough to notice that something changed in their life and notice when triggers and symptoms occur. Their “need to know” in terms of trauma story details is significantly less. Instead, what they need to know is more in the realm of what is happening now with the trauma survivor and what they can do to help when needed. A general, superficial story about the trauma will usually suffice. A good exercise is to have a client imagine frequently asked questions and come up with basic superficial answers to them. Something we try to have warfighters do prior to returning from deployment is practice a general answer to the question “what did you do in the war.” By thinking this out ahead of time they are able to give an honest but superficial answer that isn’t emotionally triggering yet tends to be enough to pacify the curious individual. Having an answer ahead of time helps avoid awkward and sometimes inappropriate responses.

Case in point – less than a month home from my own deployment I was at Thanksgiving Dinner with relatives and my aunt asked me what I did in the war. With horror, I realized I didn’t come up with my own response as I heard myself say “I watched the light in young men’s eyes die.” The conversation thus ended.

The final circle is the Outer Circle, or everyone else. They may be curious, but any details about the trauma survivor’s life is simply not their business. That doesn’t give free rein to rudeness. Just because some relative stranger is rude enough to ask you if you killed anyone during the war doesn’t mean you have the right to tell them yes and you are going to kill them next. If, however, someone in this circle witnesses significant trauma reactions, such as a flashback, a simple explanation may be necessary. This can be very simple, such as having them told by someone in a closer circle the person was badly startled, or even had a trauma response, and is fine now. If that outer circle person can assist in some way, simply let them know what to do and leave it at that.

The bottom line is this – while it is understandable that trauma survivors hesitate to share information and do have a right to keep information to themselves, some information must be shared. To manage the anxiety of this fact, clients should be encouraged to have boundaries around what information should and should not be shared and with whom. An easy way to do this, as well as to handle questions when they unexpectedly arise, is to think of people in terms of categories. Consider frequently asked questions and information to be shared ahead of time and practice responses to gain confidence and trust that information can be given within appropriate frameworks. There will still be anxiety with how to talk to people about trauma and how people will respond. But hopefully, this anxiety will be less with increased confidence that you won’t say something you don’t mean or want to.

The opinions in CDP Staff Perspective blogs are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science or the Department of Defense.

Debra Nofziger, Psy.D., is a Senior Military Behavioral Health Psychologist and certified Cognitive Processing Therapy Trainer with the Center for Deployment Psychology (CDP) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. Located in San Antonio, TX, she develops, maintains, and conducts virtual and in-person training related to military deployments, culture, posttraumatic stress, and other psychological and medical conditions Service members and veterans experience.

Previously, I wrote about why combat veterans hesitate to share details about their combat experiences. These insights could be adjusted to anyone who has experienced trauma. I’ve repeatedly had veterans, providers, and family members tell me this makes sense to them. However, understanding a hesitancy to share does not mean it is okay to tell loved ones absolutely nothing about what happened if someone is struggling with the aftermath of trauma. People have a right to their privacy and to keep certain information to themselves. Yet family and friends also have the right to know something about what is happening. So how do we help those with trauma feel more comfortable sharing their experiences with loved ones? What are the boundaries around what is told and what isn’t?

First, we need to distinguish between sharing about the trauma and sharing about the person’s trauma reactions. Symptoms, triggers, and what a person can do to help with them are not the same as telling someone the actual details of the trauma story. When someone asks for information, are they asking more for details on how they can assist in the moment or future, or about the past event itself? Emotions run high around trauma reactions, and it can be difficult in the moment to tell the difference. Learning how to really listen to the questions asked can be a way to feel more calm and in control of the situation. Often, if the person is asking a “what happened” question, it can be redirected to an “in the moment trigger” answer.

For example, if someone notices a trauma survivor is struggling after being triggered and asks if they are okay and want to talk about what happened, this could be interpreted as them asking for details of the trauma story, and indeed this could be what the person is asking for. But the trauma survivor can instead choose to answer by saying they have a trauma history and were triggered by whatever sound or thing it was. Then they can add what would help in the moment, such as they just need a few moments of quiet outside and it would be helpful for the person to be sure that no one bothers them, or runs interference by letting others who may have witnessed the event know that things are fine or make up a plausible story to cover for them. The idea is that usually a friend or bystander doesn’t need details of the trauma, but to feel they are helping the trauma survivor, so give them something that makes them feel helpful. It can be embarrassing for trauma survivors to have others witness their symptoms. But this happens. A way to handle the embarrassment is to maintain control of the information shared and what happens next.

Often, close friends and family don’t need details of the trauma story either. They may just need enough to have an idea of what happened and need more details on what symptoms the trauma survivor is going through and what they can do to best support the person. So think of this as learning how to discuss two distinct categories of trauma information – (1) the story details and (2) the trauma reaction and treatment details. For each of these, there will be boundaries about how much you give to whom. Trauma survivors never have to give all information to anyone, period. No one, no matter what they initially think, wants all the details. It isn’t healthy for either person. So how do you know how much to share? And just as critical, what don’t you share. Knowing this can make a person less concerned that they will say something by accident.

I like to have clients think of sharing information within circles of details. What they share depends on what circle a person is in. Usually by default, more of the trauma story details are shared with those closest to the individual with much less detail shared with people as they become more distant to the individual. Instead, the more distant individuals tend to get primarily trauma reaction and possibly no trauma story information. Visually, the circles of detail could look something like the bullseye seen here. Or below it, there is an inverse which visually depicts the group circles depending on how much trauma information they receive. While I’ve given labels to the circles, how a client divides things is up to them. The point is they have clear divisions between distinct groupings of people who get different levels of information.

individual with much less detail shared with people as they become more distant to the individual. Instead, the more distant individuals tend to get primarily trauma reaction and possibly no trauma story information. Visually, the circles of detail could look something like the bullseye seen here. Or below it, there is an inverse which visually depicts the group circles depending on how much trauma information they receive. While I’ve given labels to the circles, how a client divides things is up to them. The point is they have clear divisions between distinct groupings of people who get different levels of information.

The smallest group of individuals with the highest need to know is the Immediate Circle. These are the closest to the person such as a spouse or significant other and other individuals living within the home who will see the worst of what the person goes through. Because of what they will witness, they will need more information to understand and help calm their own anxiety. While deployed to a combat zone myself, I had to remind people that if they didn’t tell their loved ones any details, the only thing their families had to fill in the blanks were the things they saw on the news which was usually more alarming than reality. It is not a good idea to let people’s imaginations fill in the blanks because, even if the reality is bad, the known reality is almost always better than the unknown imagined.

That said, the details shared should never be everything. There will always be information held back which is too uncomfortable to give. It is crucial that a person defines what is important to share, what will not be shared, and then practices how to give the information in a way that relays what they want to say and with the amount of detail they want to give. Practice saying it out loud. This will build self-trust so when the time comes the desired boundaries will be set. A quick caveat about children who live in the home who are within this immediate circle. Children should not be told the same amount of detail as adults, ever. They should be told age-appropriate information and in a manner that does not frighten them about a parent’s ability to care for them. How and what to tell children should be discussed with significant others as well as child professionals as needed.

The next circle is the Inner Circle. These are still people who are very close to the trauma survivor such as immediate family and close friends. They are part of the close support system. However, they likely do not live in the same household. While it is still a good idea to tell these people details about the trauma story so their imaginations don’t get the better of them, they may not need the same details as the spouse or significant other. This is where it can get a bit strange – sometimes certain individuals in the inner circle will be privileged with more details to aspects of the story than the immediate circle. This is perfectly fine, although if this could cause friction with a spouse/significant other, how to normalize this with them is important. For example, perhaps a close friend has also experienced a traumatic event and the client feels more comfortable sharing certain details with them. Sometimes, certain individuals simply have the type of personality that makes sharing specific details easier. Whatever the reason, a client has the right to define specific individuals who are classified differently from others in terms of what information they are given. They can create completely unique circles for them that fall within and overlapping the inner and immediate circles.

Both the Immediate and Inner Circles involve a client’s closest friends, family, and immediate supports. Because of this, they need to have details about the client’s trauma reactions and what they can do to assist when needed. Consider what is likely to come up with the individuals and what they can realistically do to help.

The Daily Contact and Social Circle includes people who a person has regular contact with, but isn’t necessarily close with - casual friends, coworkers, etc. These aren’t going to be people someone calls in an emotional emergency unless absolutely no one else is available. These people know the trauma survivor well enough to notice that something changed in their life and notice when triggers and symptoms occur. Their “need to know” in terms of trauma story details is significantly less. Instead, what they need to know is more in the realm of what is happening now with the trauma survivor and what they can do to help when needed. A general, superficial story about the trauma will usually suffice. A good exercise is to have a client imagine frequently asked questions and come up with basic superficial answers to them. Something we try to have warfighters do prior to returning from deployment is practice a general answer to the question “what did you do in the war.” By thinking this out ahead of time they are able to give an honest but superficial answer that isn’t emotionally triggering yet tends to be enough to pacify the curious individual. Having an answer ahead of time helps avoid awkward and sometimes inappropriate responses.

Case in point – less than a month home from my own deployment I was at Thanksgiving Dinner with relatives and my aunt asked me what I did in the war. With horror, I realized I didn’t come up with my own response as I heard myself say “I watched the light in young men’s eyes die.” The conversation thus ended.

The final circle is the Outer Circle, or everyone else. They may be curious, but any details about the trauma survivor’s life is simply not their business. That doesn’t give free rein to rudeness. Just because some relative stranger is rude enough to ask you if you killed anyone during the war doesn’t mean you have the right to tell them yes and you are going to kill them next. If, however, someone in this circle witnesses significant trauma reactions, such as a flashback, a simple explanation may be necessary. This can be very simple, such as having them told by someone in a closer circle the person was badly startled, or even had a trauma response, and is fine now. If that outer circle person can assist in some way, simply let them know what to do and leave it at that.

The bottom line is this – while it is understandable that trauma survivors hesitate to share information and do have a right to keep information to themselves, some information must be shared. To manage the anxiety of this fact, clients should be encouraged to have boundaries around what information should and should not be shared and with whom. An easy way to do this, as well as to handle questions when they unexpectedly arise, is to think of people in terms of categories. Consider frequently asked questions and information to be shared ahead of time and practice responses to gain confidence and trust that information can be given within appropriate frameworks. There will still be anxiety with how to talk to people about trauma and how people will respond. But hopefully, this anxiety will be less with increased confidence that you won’t say something you don’t mean or want to.

The opinions in CDP Staff Perspective blogs are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science or the Department of Defense.

Debra Nofziger, Psy.D., is a Senior Military Behavioral Health Psychologist and certified Cognitive Processing Therapy Trainer with the Center for Deployment Psychology (CDP) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. Located in San Antonio, TX, she develops, maintains, and conducts virtual and in-person training related to military deployments, culture, posttraumatic stress, and other psychological and medical conditions Service members and veterans experience.