Staff Perspective: Two Weeks in Australia - A Memoir on Mitigating Jet Lag and Feeding Kangaroos

A few months ago I was fortunate enough to visit the location at the top of my travel list: Australia! Two good friends and I spent two incredible weeks in Oz. This trip required a lot of planning in the months prior, not the least of which was accounting for the long-haul flight and doing my best to prevent jet lag. Fortunately, I happen to work with several sleep experts, one of whom is also my boss. Our exchange went something like this --

Me: Would you mind looking at my plan for entraining to Australia time and giving me some suggestions?

Dr. Brim: Sure. Can you start adjusting your bed and wake time several days before? Can you change your work schedule ahead of time?

Me: That seems like that’s a question for you, Boss. Is it OK if I change my work schedule?

Dr. Brim: Yes, if you agree to write a blog about it afterwards.

Me: Only if I can include pictures of kangaroos.

Dr. Brim: Deal.

Most negotiations at CDP are similarly soul-crushing.

I don’t have to tell you that jet lag can impact the first few days of travel, regardless of whether you’re on vacation or a deployment, and even if you’re only traveling through a couple of different time zones. Many of our physical and cognitive functions are regulated by our circadian rhythm, including alertness, logical reasoning, and appetite (Kryger, Roth, & Dement, 2016). So symptoms associated with jet lag – grogginess, mood changes, fatigue – result from a systemic mismatch between our personal circadian rhythm and the local time. In general, it takes about one day to adjust to each hour of time change when traveling across time zones. But Australia was (on average) 16 hours ahead of my Eastern US time zone, so I would have been back home from vacation before I completely entrained to the local time if I didn’t try to make some adjustments ahead of time.

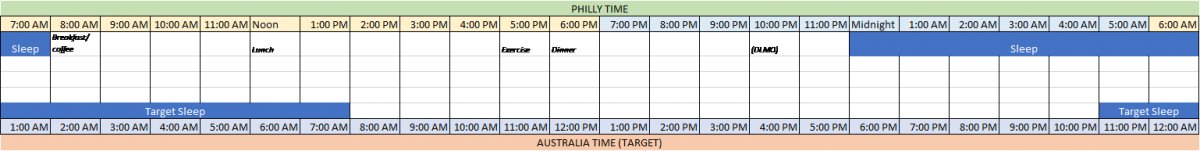

I developed a comprehensive plan for myself to follow in the days leading up to travel. The first step was to plot my current circadian rhythm and compare it to my target schedule while in Australia. This included not only bed and wake times, but also other behaviors that impact my circadian rhythm and sleep cycle, such as exercise, caffeine intake, and mealtimes. For my own awareness, I also included my assumed onset of dim light melatonin (DLMO), which typically happens about 2 hours before your natural bedtime.

(Click the image(s) below for a bigger version)

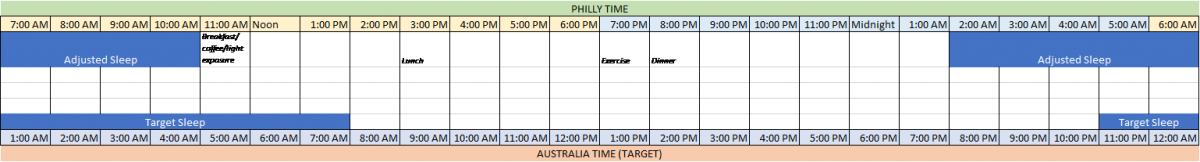

Assessing this information visually, I was relieved to find that the transition might not be as bad as I anticipated. The fact that Australia’s time zone is so far ahead actually worked in my favor, as did the fact that I’m naturally a night owl; the difference between my current sleep time and my target sleep time was only five hours. The next step, then, was to determine how many days ahead I could reasonably start prepping. Looking at my obligations the week before my travel, I could start prepping about five days before. In other words, I had five days to shift my sleep/wake schedule with the goal of getting as close to my target schedule as possible. I decided to delay my circadian rhythm by one hour every other day. That meant shifting my sleep schedule AND all of the other zeitgebers as well (“Zeitgeber” roughly translates to “time giver” and is a fancy way of referencing all of those external patterns and stimuli that help us synchronize our circadian rhythm, bright light exposure being the strongest zeitgeber). By the fourth night I had shifted my schedule to look like this:

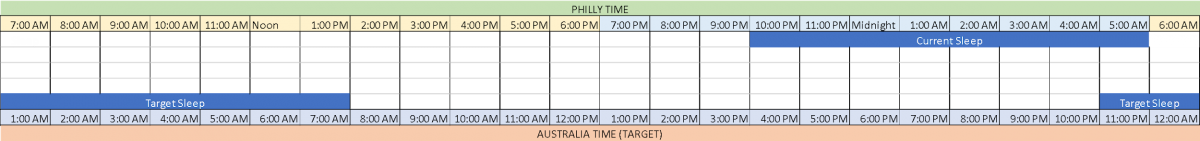

It was not too difficult to do this. Frankly, it’s a lot easier to delay your bedtime than it is to “advance” or move it earlier; you can force yourself to stay awake, but you can’t force yourself to fall asleep on cue. Although it was weird to be back to my late night college schedule, I was already two hours closer to my target schedule. But then things got tricky. I was departing the next day and traveling for a total of 32 hours door-to-door. The long-haul flight from Dallas to Sydney was 17.5 hours and that didn’t include the flights before and after. I wanted to continue to delay my bedtime during the travel day(s), but needed to account for the flights as well. I came up with the following plan:

Admittedly, managing my time on the long-haul flight triggered a great deal of anxiety, even beyond my wish to stay on a schedule. Fortunately, the travel gods smiled upon me: I had an empty seat next to me and full control over the window shade. With additional assistance from the inflight entertainment system and a prescribed sleep aid, I was able to stay awake when I wanted to and sleep when I was ready. I arrived in Australia within two hours of my target sleep time! On our first night in Australia, I forced myself to stay awake until my target bedtime. I won’t lie and say that the adjustment was seamless. It still took me another two days to fully adjust to the local time and that included a very confused appetite and several awakenings in the middle of the night. I managed the former by having lots of small snacks, which provided an opportunity to sample the local food. (Pro tip: DON’T try the Vegemite!) When I woke up in the middle of the night, I stayed in bed, kept the lights off and shades closed, and read a boring book until I fell back asleep. If you’ve attended a CBTI workshop with us, you know that those pointers violate the stimulus control rules that we put in place for the treatment of insomnia, but jet lag and insomnia are two different animals.

All in all, my acclimation to Australia’s time zone happened pretty quickly and I generally felt energetic and alert the whole time. Granted, it’s tough to feel anything less than excited when you’re snuggling koalas and hand-feeding kangaroos.

All in all, my acclimation to Australia’s time zone happened pretty quickly and I generally felt energetic and alert the whole time. Granted, it’s tough to feel anything less than excited when you’re snuggling koalas and hand-feeding kangaroos.

As I mentioned, I traveled to Oz with a couple of friends. We all shared concerns about acclimating to Australia’s time zone, so I recommended schedule adjustments for each of them, too. It was interesting to see how differently this process went for each of us. My friend, K, had a similarly easy time acclimating. She did not have the luxury of shifting her schedule ahead of time, but happened to also be a night owl, which naturally brought her closer to Australia’s schedule. She delayed her sleep as late as possible on our long-haul flight and did her best to adapt her meals and caffeine intake during the travel days as well. It took her about four days to feel fully acclimated to Australia’s time zone. Upon arriving, we both headed to the beach for a healthy dose of sunshine/bright light exposure. She and I pushed through that first night in Australia together and received accolades from the locals. While eating dinner, two Aussies expressed surprise that we were out after arriving just that morning, noting that most Americans don’t make it out of their hotels their first night in Oz. “These are AmeriCANs, not AmeriCAN’Ts!,” they claimed to our delight.

Our other friend, M, had a more difficult process. She had absolutely no flexibility in her schedule in the days leading up to our travel and is naturally an earlier sleeper. So while I started five hours away from my ideal bedtime in Australia, M started about seven hours away and could not start shifting ahead of time. Her initial sleep schedule tracked like this:

As you can see, there was virtually no overlap between her existing schedule and her target schedule. Not surprisingly, M had the most difficult time acclimating out of all of us. She napped when we arrived at our first hotel and opted to stay in that night while K and I went to dinner. M woke up the next day feeling ill with a sore throat and nasal congestion, and unfortunately that illness worsened and persisted for much of our trip. I won’t blame her illness entirely on jet lag and sleep deprivation; traveling for nearly 30 hours in a metal tube filled with compressed air is akin to sitting in a germ incubator. But we also know that aspects of our immune system are controlled by our circadian rhythm and that we become more susceptible to infections and other illnesses when that rhythm is disrupted (Paganelli, Petrarca, & Di Gioacchino, 2018). So I think it’s fair to speculate that jet lag played a role in M’s experience.

At this point you might be curious about the trip back home. BLUF: It was horrible! As I mentioned earlier, advancing your sleep-wake cycle is typically more difficult than delaying it. I could have eased the transition a bit by doing the reverse of my initial plan and advancing my bedtime by an hour every few nights towards the end of my vacation. I could have also employed OTC melatonin to advance my sleep-wake cycle. But frankly I refused to limit my experience in Australia, so I simply prepared for a rough return home. I arrived home at about 11 PM ET on a Wednesday night and was unable to fall asleep for about four hours. Although I did my best to revert to my home schedule, it took nearly a week before I could get through the day without a nap.

The next time you’re preparing to cross time zones, you may wish to make a similar plan for yourself. Of course your plan won’t look exactly like mine, even if you’re making the same trip. It’s helpful to remember that our sleep-generating ability (including how quickly you can adapt to changes in schedule and environment) and circadian preference (night owl vs early bird) are at least partly influenced by genetics, so what works for one person might not work for another. But the principles described above can help you develop an initial blueprint into which you can import your own circadian tendencies, sleep ability, and daytime obligations. Happy travels!

The opinions in CDP Staff Perspective blogs are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science or the Department of Defense.

Carin M. Lefkowitz, Psy.D., is a clinical psychologist and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Trainer at the Center for Deployment Psychology (CDP) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland.

References:

Kryger, M., Roth, T., & Dement, W. (2016). Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 6th ed. Elsevier.

Paganelli, R., Petrarca, C. & Di Gioacchino, M. (2018). Biological clocks: their relevance to immune-allergic diseases. Clinical and Molecular Allergy, 16(1).

A few months ago I was fortunate enough to visit the location at the top of my travel list: Australia! Two good friends and I spent two incredible weeks in Oz. This trip required a lot of planning in the months prior, not the least of which was accounting for the long-haul flight and doing my best to prevent jet lag. Fortunately, I happen to work with several sleep experts, one of whom is also my boss. Our exchange went something like this --

Me: Would you mind looking at my plan for entraining to Australia time and giving me some suggestions?

Dr. Brim: Sure. Can you start adjusting your bed and wake time several days before? Can you change your work schedule ahead of time?

Me: That seems like that’s a question for you, Boss. Is it OK if I change my work schedule?

Dr. Brim: Yes, if you agree to write a blog about it afterwards.

Me: Only if I can include pictures of kangaroos.

Dr. Brim: Deal.

Most negotiations at CDP are similarly soul-crushing.

I don’t have to tell you that jet lag can impact the first few days of travel, regardless of whether you’re on vacation or a deployment, and even if you’re only traveling through a couple of different time zones. Many of our physical and cognitive functions are regulated by our circadian rhythm, including alertness, logical reasoning, and appetite (Kryger, Roth, & Dement, 2016). So symptoms associated with jet lag – grogginess, mood changes, fatigue – result from a systemic mismatch between our personal circadian rhythm and the local time. In general, it takes about one day to adjust to each hour of time change when traveling across time zones. But Australia was (on average) 16 hours ahead of my Eastern US time zone, so I would have been back home from vacation before I completely entrained to the local time if I didn’t try to make some adjustments ahead of time.

I developed a comprehensive plan for myself to follow in the days leading up to travel. The first step was to plot my current circadian rhythm and compare it to my target schedule while in Australia. This included not only bed and wake times, but also other behaviors that impact my circadian rhythm and sleep cycle, such as exercise, caffeine intake, and mealtimes. For my own awareness, I also included my assumed onset of dim light melatonin (DLMO), which typically happens about 2 hours before your natural bedtime.

(Click the image(s) below for a bigger version)

Assessing this information visually, I was relieved to find that the transition might not be as bad as I anticipated. The fact that Australia’s time zone is so far ahead actually worked in my favor, as did the fact that I’m naturally a night owl; the difference between my current sleep time and my target sleep time was only five hours. The next step, then, was to determine how many days ahead I could reasonably start prepping. Looking at my obligations the week before my travel, I could start prepping about five days before. In other words, I had five days to shift my sleep/wake schedule with the goal of getting as close to my target schedule as possible. I decided to delay my circadian rhythm by one hour every other day. That meant shifting my sleep schedule AND all of the other zeitgebers as well (“Zeitgeber” roughly translates to “time giver” and is a fancy way of referencing all of those external patterns and stimuli that help us synchronize our circadian rhythm, bright light exposure being the strongest zeitgeber). By the fourth night I had shifted my schedule to look like this:

It was not too difficult to do this. Frankly, it’s a lot easier to delay your bedtime than it is to “advance” or move it earlier; you can force yourself to stay awake, but you can’t force yourself to fall asleep on cue. Although it was weird to be back to my late night college schedule, I was already two hours closer to my target schedule. But then things got tricky. I was departing the next day and traveling for a total of 32 hours door-to-door. The long-haul flight from Dallas to Sydney was 17.5 hours and that didn’t include the flights before and after. I wanted to continue to delay my bedtime during the travel day(s), but needed to account for the flights as well. I came up with the following plan:

Admittedly, managing my time on the long-haul flight triggered a great deal of anxiety, even beyond my wish to stay on a schedule. Fortunately, the travel gods smiled upon me: I had an empty seat next to me and full control over the window shade. With additional assistance from the inflight entertainment system and a prescribed sleep aid, I was able to stay awake when I wanted to and sleep when I was ready. I arrived in Australia within two hours of my target sleep time! On our first night in Australia, I forced myself to stay awake until my target bedtime. I won’t lie and say that the adjustment was seamless. It still took me another two days to fully adjust to the local time and that included a very confused appetite and several awakenings in the middle of the night. I managed the former by having lots of small snacks, which provided an opportunity to sample the local food. (Pro tip: DON’T try the Vegemite!) When I woke up in the middle of the night, I stayed in bed, kept the lights off and shades closed, and read a boring book until I fell back asleep. If you’ve attended a CBTI workshop with us, you know that those pointers violate the stimulus control rules that we put in place for the treatment of insomnia, but jet lag and insomnia are two different animals.

All in all, my acclimation to Australia’s time zone happened pretty quickly and I generally felt energetic and alert the whole time. Granted, it’s tough to feel anything less than excited when you’re snuggling koalas and hand-feeding kangaroos.

All in all, my acclimation to Australia’s time zone happened pretty quickly and I generally felt energetic and alert the whole time. Granted, it’s tough to feel anything less than excited when you’re snuggling koalas and hand-feeding kangaroos.

As I mentioned, I traveled to Oz with a couple of friends. We all shared concerns about acclimating to Australia’s time zone, so I recommended schedule adjustments for each of them, too. It was interesting to see how differently this process went for each of us. My friend, K, had a similarly easy time acclimating. She did not have the luxury of shifting her schedule ahead of time, but happened to also be a night owl, which naturally brought her closer to Australia’s schedule. She delayed her sleep as late as possible on our long-haul flight and did her best to adapt her meals and caffeine intake during the travel days as well. It took her about four days to feel fully acclimated to Australia’s time zone. Upon arriving, we both headed to the beach for a healthy dose of sunshine/bright light exposure. She and I pushed through that first night in Australia together and received accolades from the locals. While eating dinner, two Aussies expressed surprise that we were out after arriving just that morning, noting that most Americans don’t make it out of their hotels their first night in Oz. “These are AmeriCANs, not AmeriCAN’Ts!,” they claimed to our delight.

Our other friend, M, had a more difficult process. She had absolutely no flexibility in her schedule in the days leading up to our travel and is naturally an earlier sleeper. So while I started five hours away from my ideal bedtime in Australia, M started about seven hours away and could not start shifting ahead of time. Her initial sleep schedule tracked like this:

As you can see, there was virtually no overlap between her existing schedule and her target schedule. Not surprisingly, M had the most difficult time acclimating out of all of us. She napped when we arrived at our first hotel and opted to stay in that night while K and I went to dinner. M woke up the next day feeling ill with a sore throat and nasal congestion, and unfortunately that illness worsened and persisted for much of our trip. I won’t blame her illness entirely on jet lag and sleep deprivation; traveling for nearly 30 hours in a metal tube filled with compressed air is akin to sitting in a germ incubator. But we also know that aspects of our immune system are controlled by our circadian rhythm and that we become more susceptible to infections and other illnesses when that rhythm is disrupted (Paganelli, Petrarca, & Di Gioacchino, 2018). So I think it’s fair to speculate that jet lag played a role in M’s experience.

At this point you might be curious about the trip back home. BLUF: It was horrible! As I mentioned earlier, advancing your sleep-wake cycle is typically more difficult than delaying it. I could have eased the transition a bit by doing the reverse of my initial plan and advancing my bedtime by an hour every few nights towards the end of my vacation. I could have also employed OTC melatonin to advance my sleep-wake cycle. But frankly I refused to limit my experience in Australia, so I simply prepared for a rough return home. I arrived home at about 11 PM ET on a Wednesday night and was unable to fall asleep for about four hours. Although I did my best to revert to my home schedule, it took nearly a week before I could get through the day without a nap.

The next time you’re preparing to cross time zones, you may wish to make a similar plan for yourself. Of course your plan won’t look exactly like mine, even if you’re making the same trip. It’s helpful to remember that our sleep-generating ability (including how quickly you can adapt to changes in schedule and environment) and circadian preference (night owl vs early bird) are at least partly influenced by genetics, so what works for one person might not work for another. But the principles described above can help you develop an initial blueprint into which you can import your own circadian tendencies, sleep ability, and daytime obligations. Happy travels!

The opinions in CDP Staff Perspective blogs are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science or the Department of Defense.

Carin M. Lefkowitz, Psy.D., is a clinical psychologist and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Trainer at the Center for Deployment Psychology (CDP) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland.

References:

Kryger, M., Roth, T., & Dement, W. (2016). Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 6th ed. Elsevier.

Paganelli, R., Petrarca, C. & Di Gioacchino, M. (2018). Biological clocks: their relevance to immune-allergic diseases. Clinical and Molecular Allergy, 16(1).