Staff Perspective: Written Exposure Therapy (WET) - Does It Work?

Have you heard about Written Exposure Therapy (WET) yet? It’s a newer evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) for PTSD, recently added as a first line, trauma-focused treatment in the latest VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines. Last year I took the WET training taught by Dr. Brian Marx, one of the treatment originators. I must admit, I was skeptical about how it worked and whether it would be effective. Since the training, I have used it with 2 patients and now feel comfortable adding it to my PTSD toolbox.

WET is a simple and brief (five session) protocol. Patients write continuously about their target trauma for 30 minutes during each session in your office. Patients are told to write about the same trauma for all five sessions, which are 40 to 60 minutes long. The patient does no homework—none at all! This is appealing to patients since most EBPs require homework and can be daunting. Also, the therapist uses few interventions. Cognitive restructuring and processing, for example, aren’t used after the written exposures. Let me tell you more about how WET works, then review my two cases and conclude by sharing my thoughts about the treatment.

Instructions are read verbatim from the WET manual before patients begin their written narrative. In the early sessions, they are asked to write about the full trauma. In sessions four and five, patients can choose to write about just one part of the trauma and can describe how it has changed their view of life. We also ask patients for a subjective units of distress (SUD) rating on a scale from 0 to 100 immediately before and after they write their account. Patients are told not to worry about grammar or spelling and to focus on their deepest thoughts and feelings.

After the patient writes for 30 minutes in each session, the therapist inquires how the writing experience went. We don’t read the written account at that time, ask about the content or try to process the memory with the patient. Rather, the goal is to briefly check in about the patient’s engagement in the writing process. Before wrapping up each session, the patient is told they’ll likely experience thoughts, feelings and images related to the trauma during the upcoming week. They’re encouraged not to push these reactions away. Once the patient leaves the session, the therapist reads their written narrative in order to provide minimal feedback at the start of the next session. We don’t read it to facilitate new learning or point out stuck points. When feedback is shared next time, we keep these kinds of questions in mind:

- Did the patient follow the instructions by focusing on thoughts and feelings or did they only recount the facts?

- Did the patient stick to the target trauma or did they move onto another one?

- Did the patient only write a few sentences or did they demonstrate engagement in the memory by writing several paragraphs?

My WET Cases

I received permission from my two patients to describe their treatment below and have de-identified their personal information. My first patient, David, followed the standard protocol. My second patient, Nathaniel, required modifications. Ultimately, both improved, which was rewarding for me and life-enhancing for them. Not only did their PTSD symptoms decrease significantly but so did their depression and insomnia-related symptoms. In WET, clinicians don’t necessarily track these other symptoms but because my patients were struggling with depression and sleep, this made sense to me.

David

A male firefighter in his twenties with a work-related index trauma when he witnessed the death of a person after he and his team tried to save the victim and then had to share the news with a relative. David engaged in consecutive weekly WET sessions except we skipped three weeks between sessions four and five because of a change in his work schedule. Significant gains were made by the end of session five and therapy was terminated per the protocol. Aside from one PTSD evaluation/treatment planning session, we only met for the five WET sessions. David chose WET because it was a shorter and less time intensive than Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE). David reported finding WET very beneficial and wished he had sought care earlier. He described it giving him a greater sense of control over the trauma memory and allowing him to understand the impact it had on him better.

David’s SUD ratings decreased between sessions as follows:

- WET session #1: pre-written narrative = 40; post-written narrative = 45

- WET session #5: pre-written narrative = 10; post-written narrative = 10

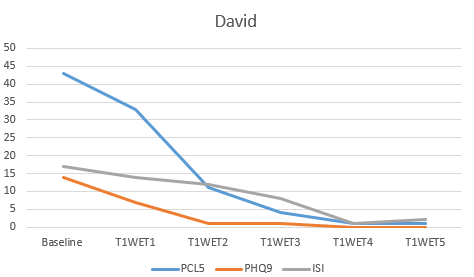

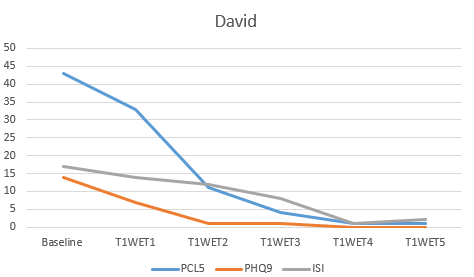

PTSD, depression and insomnia self-report measures (the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist 5: PCL-5; Patient Health Questionnaire 9: PHQ-9; and Insomnia Severity Index: ISI) were completed by David at baseline and before each WET session. His scores are graphed below.

*Scores are not to scale because the 3 sets of results are all on 1 graph.

Nathaniel

A male veteran in his sixties with multiple traumas throughout his life. Prior to WET, we engaged in supportive counseling incorporating healthy coping strategies, journal writing, sleep hygiene tips, PTSD psychoeducation and basic CBT skills. Later, the patient agreed to try WET. His index trauma was trying to stop an individual from escaping a crime scene where Nathaniel was severely injured. Because Nathaniel’s PTSD symptoms did not decrease as much expected, we added a sixth session to the regular WET protocol. Subsequently, we met to discuss treatment progress and collaboratively decided it would be worth targeting a childhood trauma through WET. Two weeks later he began a second round of WET focused on his most distressing childhood trauma. He engaged in five weekly sessions of WET on the second trauma, then we skipped one week, and had a final sixth WET session. Three weeks later we reviewed treatment progress and decided to terminate therapy because solid progress had been made.

Nathaniel found WET helpful. It allowed him to accept what had happened from a more balanced perspective and realize he can move forward while carrying trauma-related scars. He discovered he is not alone in his traumas; deserves to focus on himself; no longer needs to constantly try to fix and protect other people and can trust some individuals. He can make choices in his life now that don’t have to be dictated by past traumas. He is looking forward to enjoying more of life and is less triggered and worried about what others think of him.

Nathaniel’s SUD ratings changed between sessions as follows:

- WET session #1 Trauma 1: pre-written narrative = 40; post-written narrative = 60

- WET session #6 Trauma 1: pre-written narrative = 5; post-written narrative = 20

- WET session #1 Trauma 2: pre-written narrative = 35; post-written narrative = 70

- WET session #6 Trauma 2: pre-written narrative = 10; post-written narrative = 50

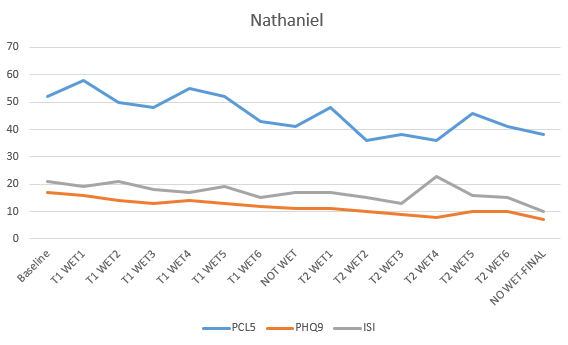

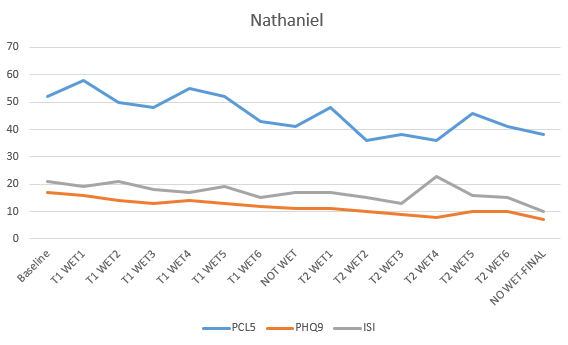

PTSD, depression and insomnia self-report measures (the same as noted above) were completed by the Nathaniel at baseline, before each WET session, in between the two iterations of WET and at the termination session. His scores are graphed below.

*Scores are not to scale because the 3 sets of results are all on 1 graph.

My Thoughts about WET

While the WET manual is simple and quick to read, I wanted more direction about how to handle common challenges in treatment. For example, I would have liked information about how to handle the sessions when my patients’ SUD ratings were not decreasing as much as expected. Also, although the manual referred to repeating a session if a patient has not followed the instructions, this was not elaborated upon so it was difficult to decide whether to do this. Moreover, in a few sessions with Nathaniel, the 30 minutes of writing did not seem long enough since he finished when his SUD levels were high and told me afterwards that he was just getting to the threatening or disturbing part of the memory. Giving him more time to write his narratives would have been beneficial, but I was uncertain if I could do this. Additionally, when I modified the protocol by doing another round of WET on a second trauma with him, the manual provide little instruction about how to build on the earlier sessions focused on the first trauma. The manual was overly simplistic when it came to terminating the therapy as well. I wanted more guidance about how to wrap up the treatment and help my patients consider next steps and engage in relapse prevention.

It was also very challenging not to support my patients in emotionally processing and cognitively restructuring their trauma-related beliefs while delivering this protocol. I felt handicapped after they had written their narratives. At times I slipped into these modes, and I remain confused why this is not recommended, particularly if it surfaces naturally with a patient. I wonder if these shortcomings may contribute to less long-lasting gains. How durable are the results? Indeed, this treatment may be more effective for patients with less chronic PTSD, like David, because the limited doses of exposure and lack of cognitive restructuring work make it difficult to help patients fully address and modify unhelpful enduring beliefs.

At the same time, I think WET is a rather benign approach that can be quite useful for some patients—probably those with less severe PTSD symptoms. If it doesn’t help or is not enough, WET may serve as a primer or stepping stone for a more demanding and intensive trauma-focused EBP like PE or Cognitive Processing Therapy. I hope sharing my experiences treating David and Nathaniel encourages you to learn more about WET.

The title of the WET manual is: Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD: A Brief Treatment Approach for Mental Health Professionals by Brian P. Marx and Denise M. Sloan.

The Center for Deployment Psychology will be hosting a Written Exposure Therapy (WET) in-person training April 17th, 2020 at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Tacoma, Washington. This training will be conducted by WET Co-Creator Dr. Brian Marx and will be open to all mental health providers. If you are interested in attending this training please contact Project Manager Jeremy Karp at jkarp@deploymentpsych.org.

The opinions in CDP Staff Perspective blogs are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science or the Department of Defense.

Paula Domenici, Ph.D., is the Director of Training and Education with the Center for Deployment Psychology (CDP) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. Dr. Domenici oversees the development of courses and training programs for providers on evidence-based treatments for Service members and Veterans

Have you heard about Written Exposure Therapy (WET) yet? It’s a newer evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) for PTSD, recently added as a first line, trauma-focused treatment in the latest VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines. Last year I took the WET training taught by Dr. Brian Marx, one of the treatment originators. I must admit, I was skeptical about how it worked and whether it would be effective. Since the training, I have used it with 2 patients and now feel comfortable adding it to my PTSD toolbox.

WET is a simple and brief (five session) protocol. Patients write continuously about their target trauma for 30 minutes during each session in your office. Patients are told to write about the same trauma for all five sessions, which are 40 to 60 minutes long. The patient does no homework—none at all! This is appealing to patients since most EBPs require homework and can be daunting. Also, the therapist uses few interventions. Cognitive restructuring and processing, for example, aren’t used after the written exposures. Let me tell you more about how WET works, then review my two cases and conclude by sharing my thoughts about the treatment.

Instructions are read verbatim from the WET manual before patients begin their written narrative. In the early sessions, they are asked to write about the full trauma. In sessions four and five, patients can choose to write about just one part of the trauma and can describe how it has changed their view of life. We also ask patients for a subjective units of distress (SUD) rating on a scale from 0 to 100 immediately before and after they write their account. Patients are told not to worry about grammar or spelling and to focus on their deepest thoughts and feelings.

After the patient writes for 30 minutes in each session, the therapist inquires how the writing experience went. We don’t read the written account at that time, ask about the content or try to process the memory with the patient. Rather, the goal is to briefly check in about the patient’s engagement in the writing process. Before wrapping up each session, the patient is told they’ll likely experience thoughts, feelings and images related to the trauma during the upcoming week. They’re encouraged not to push these reactions away. Once the patient leaves the session, the therapist reads their written narrative in order to provide minimal feedback at the start of the next session. We don’t read it to facilitate new learning or point out stuck points. When feedback is shared next time, we keep these kinds of questions in mind:

- Did the patient follow the instructions by focusing on thoughts and feelings or did they only recount the facts?

- Did the patient stick to the target trauma or did they move onto another one?

- Did the patient only write a few sentences or did they demonstrate engagement in the memory by writing several paragraphs?

My WET Cases

I received permission from my two patients to describe their treatment below and have de-identified their personal information. My first patient, David, followed the standard protocol. My second patient, Nathaniel, required modifications. Ultimately, both improved, which was rewarding for me and life-enhancing for them. Not only did their PTSD symptoms decrease significantly but so did their depression and insomnia-related symptoms. In WET, clinicians don’t necessarily track these other symptoms but because my patients were struggling with depression and sleep, this made sense to me.

David

A male firefighter in his twenties with a work-related index trauma when he witnessed the death of a person after he and his team tried to save the victim and then had to share the news with a relative. David engaged in consecutive weekly WET sessions except we skipped three weeks between sessions four and five because of a change in his work schedule. Significant gains were made by the end of session five and therapy was terminated per the protocol. Aside from one PTSD evaluation/treatment planning session, we only met for the five WET sessions. David chose WET because it was a shorter and less time intensive than Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE). David reported finding WET very beneficial and wished he had sought care earlier. He described it giving him a greater sense of control over the trauma memory and allowing him to understand the impact it had on him better.

David’s SUD ratings decreased between sessions as follows:

- WET session #1: pre-written narrative = 40; post-written narrative = 45

- WET session #5: pre-written narrative = 10; post-written narrative = 10

PTSD, depression and insomnia self-report measures (the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist 5: PCL-5; Patient Health Questionnaire 9: PHQ-9; and Insomnia Severity Index: ISI) were completed by David at baseline and before each WET session. His scores are graphed below.

*Scores are not to scale because the 3 sets of results are all on 1 graph.

Nathaniel

A male veteran in his sixties with multiple traumas throughout his life. Prior to WET, we engaged in supportive counseling incorporating healthy coping strategies, journal writing, sleep hygiene tips, PTSD psychoeducation and basic CBT skills. Later, the patient agreed to try WET. His index trauma was trying to stop an individual from escaping a crime scene where Nathaniel was severely injured. Because Nathaniel’s PTSD symptoms did not decrease as much expected, we added a sixth session to the regular WET protocol. Subsequently, we met to discuss treatment progress and collaboratively decided it would be worth targeting a childhood trauma through WET. Two weeks later he began a second round of WET focused on his most distressing childhood trauma. He engaged in five weekly sessions of WET on the second trauma, then we skipped one week, and had a final sixth WET session. Three weeks later we reviewed treatment progress and decided to terminate therapy because solid progress had been made.

Nathaniel found WET helpful. It allowed him to accept what had happened from a more balanced perspective and realize he can move forward while carrying trauma-related scars. He discovered he is not alone in his traumas; deserves to focus on himself; no longer needs to constantly try to fix and protect other people and can trust some individuals. He can make choices in his life now that don’t have to be dictated by past traumas. He is looking forward to enjoying more of life and is less triggered and worried about what others think of him.

Nathaniel’s SUD ratings changed between sessions as follows:

- WET session #1 Trauma 1: pre-written narrative = 40; post-written narrative = 60

- WET session #6 Trauma 1: pre-written narrative = 5; post-written narrative = 20

- WET session #1 Trauma 2: pre-written narrative = 35; post-written narrative = 70

- WET session #6 Trauma 2: pre-written narrative = 10; post-written narrative = 50

PTSD, depression and insomnia self-report measures (the same as noted above) were completed by the Nathaniel at baseline, before each WET session, in between the two iterations of WET and at the termination session. His scores are graphed below.

*Scores are not to scale because the 3 sets of results are all on 1 graph.

My Thoughts about WET

While the WET manual is simple and quick to read, I wanted more direction about how to handle common challenges in treatment. For example, I would have liked information about how to handle the sessions when my patients’ SUD ratings were not decreasing as much as expected. Also, although the manual referred to repeating a session if a patient has not followed the instructions, this was not elaborated upon so it was difficult to decide whether to do this. Moreover, in a few sessions with Nathaniel, the 30 minutes of writing did not seem long enough since he finished when his SUD levels were high and told me afterwards that he was just getting to the threatening or disturbing part of the memory. Giving him more time to write his narratives would have been beneficial, but I was uncertain if I could do this. Additionally, when I modified the protocol by doing another round of WET on a second trauma with him, the manual provide little instruction about how to build on the earlier sessions focused on the first trauma. The manual was overly simplistic when it came to terminating the therapy as well. I wanted more guidance about how to wrap up the treatment and help my patients consider next steps and engage in relapse prevention.

It was also very challenging not to support my patients in emotionally processing and cognitively restructuring their trauma-related beliefs while delivering this protocol. I felt handicapped after they had written their narratives. At times I slipped into these modes, and I remain confused why this is not recommended, particularly if it surfaces naturally with a patient. I wonder if these shortcomings may contribute to less long-lasting gains. How durable are the results? Indeed, this treatment may be more effective for patients with less chronic PTSD, like David, because the limited doses of exposure and lack of cognitive restructuring work make it difficult to help patients fully address and modify unhelpful enduring beliefs.

At the same time, I think WET is a rather benign approach that can be quite useful for some patients—probably those with less severe PTSD symptoms. If it doesn’t help or is not enough, WET may serve as a primer or stepping stone for a more demanding and intensive trauma-focused EBP like PE or Cognitive Processing Therapy. I hope sharing my experiences treating David and Nathaniel encourages you to learn more about WET.

The title of the WET manual is: Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD: A Brief Treatment Approach for Mental Health Professionals by Brian P. Marx and Denise M. Sloan.

The Center for Deployment Psychology will be hosting a Written Exposure Therapy (WET) in-person training April 17th, 2020 at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Tacoma, Washington. This training will be conducted by WET Co-Creator Dr. Brian Marx and will be open to all mental health providers. If you are interested in attending this training please contact Project Manager Jeremy Karp at jkarp@deploymentpsych.org.

The opinions in CDP Staff Perspective blogs are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science or the Department of Defense.

Paula Domenici, Ph.D., is the Director of Training and Education with the Center for Deployment Psychology (CDP) at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. Dr. Domenici oversees the development of courses and training programs for providers on evidence-based treatments for Service members and Veterans